In an ideal world, red beryl would be prized just for what it is. And what it is, to quote Gem and Gemology’s landmark 1984 article on this Utah stone, “is the rarest of all gem beryl.” But because this is a far-from-ideal world where hardly any jewelers, let alone consumers, have a nodding acquaintance with it, red beryl is prized for what it isn’t: emerald. Or wasn’t.

Named “bixbite” in 1912 and unsellable ever since as such, a few dealers have recently found they can make mini-markets in this beryl by selling it to collectors as red emerald. Although this tactic infuriates many in the trade, marketers say they have no choice. Being a beryl just doesn’t excite potential buyers. Being an emerald does. Besides, these sellers ask, what harm is done since the two gems are members of the same family? Hmm…

While the two share family ties, the relationship is more like that of cousins than siblings. And there’s the rub. For the past few centuries, the word “emerald,” derived from the Greek word smardagus, has referred to a wide, but by no means complete, gamut of green beryls (today it refers to green beryls with chromium). Before that, however, smardagus included nearly every green gem known. Hence, some gemologists think it stretching terms to suddenly make a word that has long meant “green” also mean “red.”

But, hey, we’re not talking gemology here. We’re talking gem marketing. In this sphere, it is kosher to substitute the name of a gem species’ most popular variety for its family name. Or so say defenders of the name “red emerald.” Isn’t, they ask, every variety of corundum, except ruby and padparadscha, called “sapphire”—despite the fact that the original word for sapphire, sapphirus, meant blue? And didn’t the Tanzanian government christen a rare green zoisite with the name “tanzanite”—despite the fact that the name referred solely to the blue variety of zoisite?

Well, if words for blue can take on chameleon qualities, surely words for green can also. “Which would you rather buy: blue beryl or aquamarine?” asks Ray Zajicek, the Dallas dealer who coined the name “red emerald” in 1990. “Aquamarine, of course. So why buy red beryl when you can buy red emerald?”

Zajicek is convinced that without the name of “red emerald,” connoisseurs wouldn’t be paying over $10,000 per carat for fine-color, eye-clean 1-carat sizes of this gem. Is greater salability reason enough to play name games with emerald?

Conversation Peace

At present, most gem dealers are opposed to the name “red emerald,” although many are determined to stay neutral on the matter. “I don’t like taking liberties with gem names,” says one, “but you’ve got to admit that ‘red emerald’ works wonders.”

Rex Harris, the owner of the world’s only significant gem-producing red beryl locality in the Wah Wah Mountains of Utah, 250 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, says it doesn’t matter to him what red beryl is called. Nevertheless, he has filed for a trademark name on this gem that would give him the right to sell it as “red emerald.” In defense of this action, he claims the U.S. Trade Mark Office has already approved the trade names of “blue emerald” and “pink emerald” (aquamarine and morganite, respectively).

No surprise there. From a marketing standpoint, changing the name of “beryl” to “emerald” is as much a stroke of brilliance as was changing the name “Frances Gumm” to “Judy Garland.” But naming gems and minerals is not wholly a matter of inspiration. These are very weighty matters, often decided by international committees. For such a committee to accept red emerald, there would have to be gemological justification. Is there?

Zajicek says there is, pointing out that both red beryl and emerald contain the element chromium. However, while chromium acts as a greening agent in beryl, it does not act as a reddener in beryl the way it does in corundum. Red beryl, like morganite (pink beryl), owes its color to manganese. So traces of chromium don’t by themselves qualify this gem for the name of “emerald.”

Are there other gemological grounds? Except for two-phase inclusions common to Zambian and Brazilian emerald, there are none, say experts we talked to. Thus “red emerald” is likely to be vetoed, even censured, if marketers petition trade groups for approval of the name. For sure, the name will never be condoned in gemologist circles. But that probably won’t matter much to marketers of red emerald. Only official disapproval of the name, say by a board vote of the American Gem Trade Association or an opinion letter from the Federal Trade Commission, is likely to deter further use of the name.

Ripple Effects

What has kept the controversy over red emerald from erupting into a full-scale nomenclature war is the fact that only around 500 medium-to-fine quality red beryls are cut every year in sizes between 20 points and 1 carat (larger stones are extremely rare). But since prices for clean, top-color red beryls in ½-carat sizes range from $5,000 to $7,000 per carat, dealers who don’t sell this gem wonder whether their heady prices are based on gimmickry rather than rarity. Would these gems fetch anywhere near the prices they do if sold as beryl?

The question is hard to answer because every major marketer of red beryl sells it as emerald. Indeed, the biggest of them, Fred Rowe, House of Onyx, Greenville, Ky., lists the gem as “American red emerald” in his mailers. Zajicek, the second most important marketer,calls it simply “red emerald” when showing it to his main customers for this gem: Japanese connoisseurs.

The pity of all this is that red beryl, at its best, is an ideal collector’s stone. Generally as included as emerald, red beryl that is clean is very hard to find. Easier to find are ideal colors which resemble the pinkish-red hues of the recently discovered Vietnamese ruby that dealers love. Supply is so limited that fewer than 10,000 stones are cut a year, more than 95% of them melee (wholesaling for $200 to $300 per carat in better to fine grades). Last but not least, only the Wah Wah Mountains afford produces cuttable stones, making this a U.S. exclusive. Aren’t these factors enough to ignite collector passion?

“Collectors have long appreciated red beryl for its rarity, beauty and origin,” says Michael Randal, Crystal Reflections, San Anselmo, Calif. “Calling it ‘red emerald’ doesn’t add anything to its value or reputation. It just makes buyers suspicious.”

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

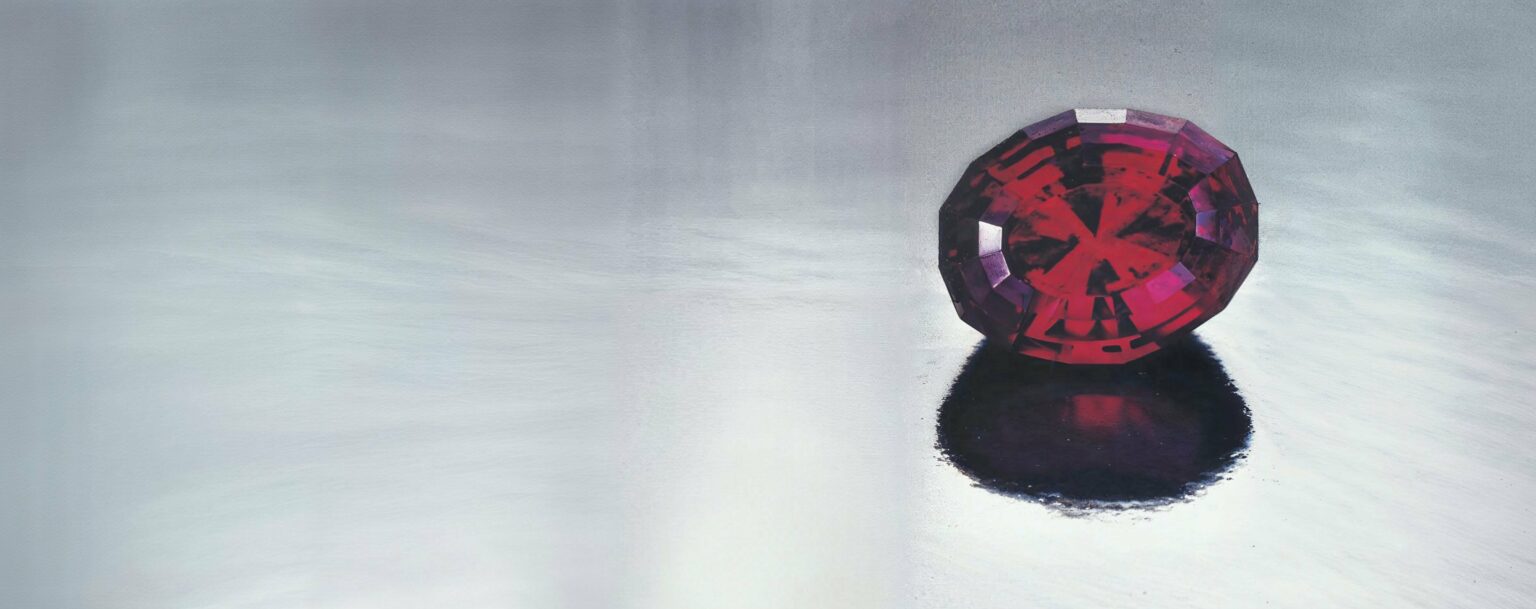

The 1.59-carat red beryl shown in the header is courtesy of Rex Harris, Delta, Utah. It was faceted by Tina Neilson.