When it comes to value based purely on measurable factors like color or clarity, gemologists point to the diamond world as a role model for a new rationalism. Fittingly, this rationalism shuns the romantic notion that stones are worth more due to suspected but hard-to-prove origin at a hallowed historic site. The diamond world, gemologists will tell you with the zeal of temperance workers, has sobered on the mystique of place.

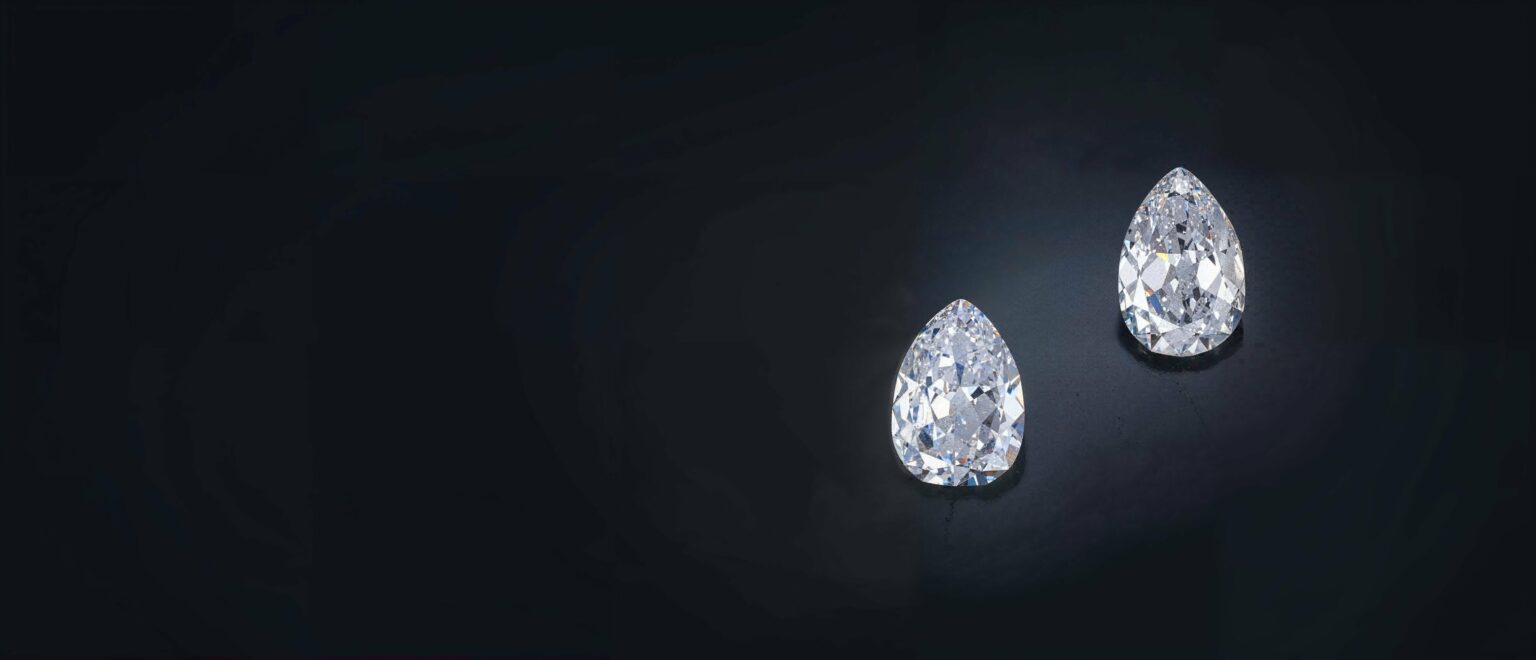

Yet when this new abstinence faced a major test in October 1990, it failed miserably. That month, Christie’s New York sold two D/VSI (potentially flawless) pear-shaped diamonds weighing 27.72 and 33.83 carats for $3.3 million—by slyly implying they were from India’s Golconda region—the most revered diamond deposit of all time. To even hint stones hail from this alluvial source is to imbue them with powerful historical significance.

However, because the auction house lacked proof these stones were from Golconda, hint is all it could do. Indeed, Christie’s side-stepped its provenance problem by publishing a general essay on the Golconda breed in its catalog for the sale of the two pear shapes. Never once did the essay refer to the diamond duo that prompted its writing. But the inference to be drawn was clear: both stones fit squarely in the Golconda mold.

In this case, that mold transcends origin. Rather, contended the essay’s author, jewelry historian Mary Murphy Hammi, the term “Golconda” is a “varietal” and not a place name that refers to stones with a certain prized appearance.

Perhaps. But many connoisseurs still hooked on the mystique of place didn’t make pilgrimages to Christie’s just to admire stones that look a certain way. They went there to gaze close up at an almost perfectly matched pair of colorless diamonds that instinct assured them came from the riverbeds of ancient India. Connoisseurs rationalized it didn’t matter if Christie’s refused to certify the stones as Golconda. They were just playing it safe. After all, you can’t be 100% sure about these things.

OK, countered anti-origin gemologists, then why broach the subject of Golconda in the first place? Why, indeed?

If nothing else, the Christie’s sale reignited a major gem trade controversy. Given the auction house’s caginess with the term “Golconda,” are gemologists correct in wanting to disabuse the diamond world of the rarely verifiable criterion of origin?

A Synonym for Perfection

Say the word “Golconda” to a jewelry connoisseur and his response may very well be a Pavlovian quickening of the pulse. For Golconda is to diamond what Burma is to ruby and Kashmir is to sapphire. More than just the supreme source for this gem, the term “Golconda” is a synonym for perfection, an excuse for the highest expectations of a diamond. Why?

In her essay for Christie’s, Hammi described Golconda diamonds as ones that possess “superb luminousness and transparency.” Others call this trait “limpidity.” But whatever words you choose, the end-result, as Hammi wrote, “is a quality to which light appears to pass through the stone as if it were totally unimpeded, almost as if the light were passing through a vacuum.” Add in what Hammi felt a softer “surface luster,” in part a function of older cutting styles, and you have the ultimate in beauty for colorless diamonds.

For some commentators, however, the magic of Golconda stones has mainly to do with color. In his “Connoisseur’s Guide to Gems and Jewels,” gem dealer Benjamin Zucker notes, while discussing diamonds that merit GIA’s top color grade of D: “White as that is, however, the old Golconda stones were by comparison ‘whiter than white.’ Place a Golconda diamond from an old piece of jewelry alongside a modern, recently cut D-color diamond, and the purity of the Golconda stone will become evident.”

And how! A 1-carat-plus pear shape I saw six years ago was so splendidly crystalline that it made its owner’s D-color masterstone (a stone graded by GIA for comparisons with other diamonds) seem slightly grayish. At first, I thought this stone, introduced as a “super D,” owed its beauty to fluorescence, a phenomenon that often makes colorless diamonds seem blue-white in daylight. But that wasn’t the case. Baffled, I asked if the diamond was from Golconda. The dealer had no idea what I was talking about. The stone, he said, was a re-cut. But I am convinced I was looking at a bona fide Golconda.

However, just because a diamond is a so-called “super-D” is no guarantee that it is Golconda in essence—or even spirit. Hammi believes that color is only part of the equation of Golconda beauty. “I’ve seen the incredible transparency that people say is characteristic of Golconda diamonds, in stones the GIA graded G and H,” she says. Usually, though, magnificent Golconda stones warrant D to F color grades.

No Cause for Celebration

The problem with the Golconda mystique is that it leads one to expect a superior diamond, even though many drab diamonds in jewelry made before 1700 technically qualify as Golconda stones, at least in origin. Truly colorless diamonds were as rare in India as anywhere else. Or so reading the only known-in-depth account of Indian diamond mining, found in a 1676 narrative called “Travels in India,” indicates. Written by the famous French jeweler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, the book describes the highlights of his six trips to India between 1630 and 1668, during which he was shown many of India’s greatest diamonds, including the Koh-i-noor, the Regent and the Great Mogul. During Tavernier’s time, India seems to have just passed it’s peak diamond production years, generally believed to be its 15th, 16th and early 17th centuries—although mining is recorded as early as 800 B.C.

Fortunately, the Frenchman found things far more encouraging in the diamond-rich Golconda district in what is today the state of Hyderabad—then by far the most active of India’s five diamond regions. At the district’s Kollur alluvial deposits alone, Tavernier saw 60,000 diamond diggers and washers at work before traveling to the district’s diamond trading center and capital, also known as Golconda. But whether the Golconda district was always India’s leading diamond producing area isn’t known.

Whatever the case, attributes of Golconda’s finest diamonds earned the locality a fame never equaled by any other Indian diamond region. Over time, the term “Golconda” came to represent the glories of Indian stones. It remains to be seen if the name will continue to work its magic in the future.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The two diamonds shown in the header weigh 27.72 and 33.83 carats and are courtesy of Christie’s New York.