The world of phenomenon gems was dealt a severe blow when Sri Lanka’s deposit of “blue-sheen” moonstone ran dry around 1988. Suddenly, jewelers were without the feldspar moonstone’s family name—that best displays the special color-play effect called “adularescence” for which this gem family is most known.

Fortunately, the blow was softened by the discovery of a fellow feldspar in southern India. Unfortunately, the trade has been calling the new material “rainbow moonstone.”

Right church, wrong pew.

According to Swiss geologist/gemologist Dr. Henry Hanni, the first scientist to have done extensive chemical analysis of the species, the Indian gemstone belongs to the labradorite branch of the feldspar family while moonstone belongs to the orthoclase branch. The reason: traces of albite and “anorthite”. For this reason, the stone should properly be called “rainbow labradorite” rather than “rainbow moonstone.”

But it won’t be. The name “moonstone” sounds better. And, besides, the two gems are kissing cousins.

In any case, India’s new labradorite is rapidly catching on as a replacement for blue-sheen moonstone or, failing that, a consolation for its loss. And no wonder. The former shows the same kind of spectacular color reflections as the latter— only in multi-colors. That’s good news for lovers of “adularescence (an optical effect unique to feldspar caused by light interference from its tightly layered crystal structure). Just remember to call it “labradorescence,” please, the counterpart to “adularescence” on the labradorite side of the feldspar family.

As for those who can’t imagine being consoled for the absence of midnight-blue moonstone by a kaleidoscopic-colored labradorite, consider this a possible solace: Rainbow labradorite sometimes boasts a predominant electric-blue color.

There’s only one wrinkle in all this good news from the feldspar front. Rainbow labradorite is fast becoming as hard to find in top grades as the blue- sheen moonstone it replaced. Given the circumstances under which it is mined, it is surprising there is even the little there is.

Après le Deluge

Rainbow labradorite’s only known deposit so far is a rice paddy in the monsoon – swept coastal lowlands of southwest India off the junction of the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. When the paddy isn’t submerged in flood waters (usually through June and July), it is being cultivated or harvested. That leaves about four months for mining, says moonstone specialist, Manu Nichani, Temple Trading Co., Encinitas, Calif.

After the feldspar was first discovered around 1979, and, indeed, until 1986, these four months were ample time to meet very limited demand for this curiosity stone. Nichani and other early importers to this country of rainbow labradorite remember selling top-quality stones for as little as $2 per carat around 1980. But gradually as dealer stocks of Sri Lanka’s blue-sheen moonstone started to disappear, replenishment became possible only by shifting to the new Indian material.

Even before the great dearth of moonstone, however, Nichani found himself pitted against astute, pay-any-price buyers from Idar-Oberstein, Germany. The presence of German buyers, in addition to Indians and Americans, put pressure on rainbow labradorite’s miners to produce more goods. Since they lacked sophisticated mining equipment, they had no choice but to use even more dynamite than they had already been using. This unearthed more rough, all right, but pieces remained small and fracture-laden. “At least 75% of the polished goods I see are under 2 carats,” Nichani says. “That’s why per-carat prices for 3-carat stones often triple those of 1-carat sizes.”

As of mid-1992, rapidly spiraling per-carat prices for fine rainbow labradorite are as follows: $25 to $45 for 1- to 3-carat sizes; $85 to $150 for 3- to 5-carat sizes, and $200 to $350 for sizes over 5 carats. Expect to pay far less for top colors when stones are flawed. Such prices exceed the lofty levels attained by Sri Lankan blue-sheen moonstone before its demise.

The Hue Factor

The value of rainbow labradorites has much to do with predominant hue. Although color preferences are different from country to country and are subject to change, right now the pecking order for predominant colors in America is as follows: electric blue, lavender, bluish green, purple, yellowish green and brownish red. Ironically, the most often requested colors are those least often found, prompting one to ask if people have an innate sixth sense for rarity or if nature is just an intentionally perverse provider.

In any case, demand for rainbow labradorite has soared so swiftly that many dealers think it is poised to become the gem world’s favorite feldspar—despite breathtaking prices. Some, like Sri Lankan gem specialist Michael Schramm, who spends half the year abroad and the other half in Boise, Idaho, think it might already have overtaken moonstone in popularity.

Having said this, it is important to remind readers that the dimensions of demand for feldspar don’t approach anywhere near those for phenomenon-stone standbys such as opal. We doubt that this one-deposit gem could even support such popularity. Almost of necessity, it is considered mostly a boutique gem. But dealers like Nichani are encouraged by the growing numbers of ordinarily conservative New York jewelry manufacturers who are experimenting with calibrated rainbow labradorites, especially in 6mm x 4mm to 7mm x 5mm ovals and 6mm to 8mm rounds—all in sizes under 2 carats, for which supply is not quite as crimped as it is for larger stones.

Even more encouraging to him is the exponential jump in demand from Hawaii, demand he says that is as great as it is anywhere in the mainland U.S. To Nichani, this suggests that the greatest admirers of phenomenon gems in the world, the Japanese, are about to go mad for rainbow labradorite. “With so many of my best stones going to Honolulu,” he explains, “I have to assume that most of them are going to tourists. Since the Japanese are the biggest tourist group there now, I’ve got to suspect their interest in the gem is behind the surge in sales to Hawaii.”

Meanwhile, back on the mainland, Nichani is exploring sales to still another hot market: enthusiasts of “touchie-feelie” gems and jewelry. Indeed, interest has been so keen from makers of crystal jewelry that he showed his wares at the Crystal Congress in Los Angeles in July of 1989. “There are so many directions for this gem to take off in that I’ve started a cutting factory for both calibrated and free sizes in India,” Nichani says. But with rough now so sparse, his workers spend most of their time with other gems.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

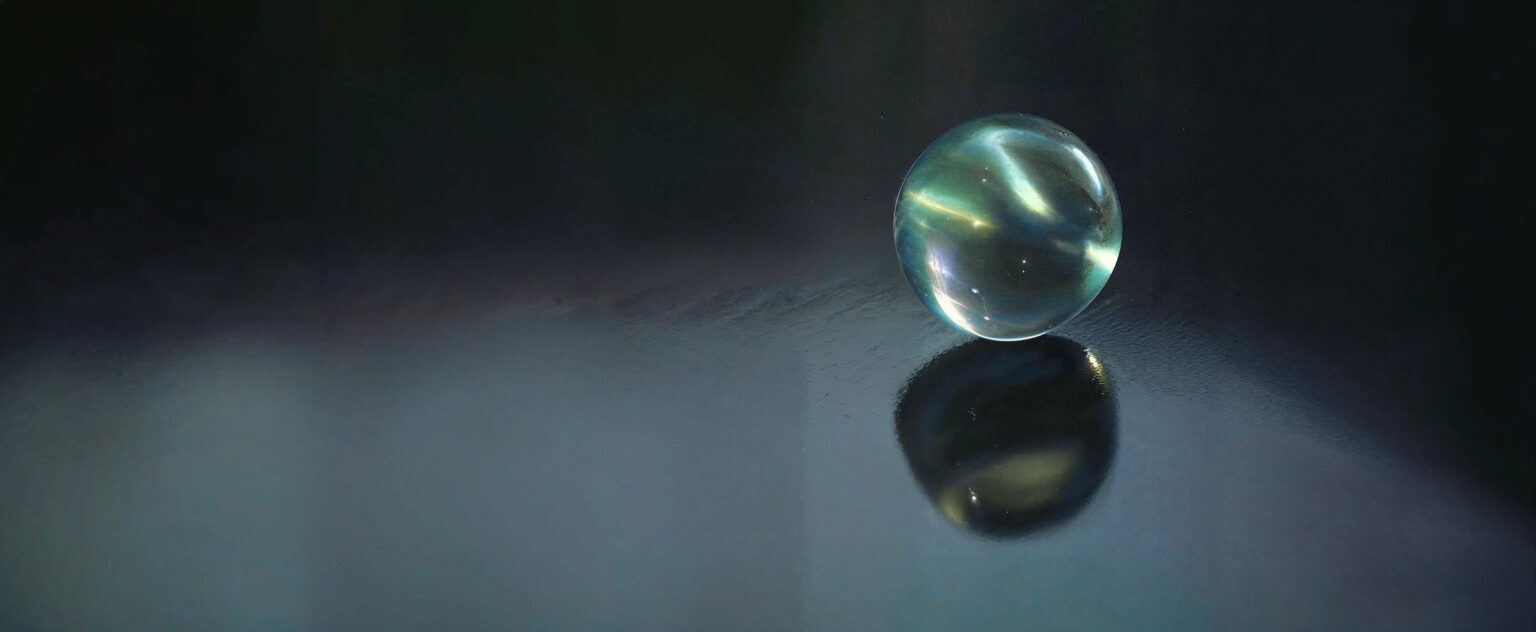

The 18-carat rainbow labradorite shown in the header image is courtesy of Temple Trading Co., Encinitas, Calif.