The world has lived so long with a 2,500-plus Dow Jones average that it comes as a shock to be reminded this bellwether index for the U.S. stock market didn’t top 1,500 until 1983 and 2,000 until 1986. And when you are told that the average sank to 577 in 1973 during a recession far milder than that of 1990-92, your brain feels like a gong in a Buddhist monastery. Numbers that low are just too bad to be true.

Now imagine the reaction of some minds when quoted recent prices—said to have reached $10,000 per carat—for a strain of neon-glowing tourmalines from Brazil’s Paraiba mining district, discovered in 1989. Numbers that high are just too good to be true. Yet dealers offer to swear on the Bible that such prices were matters of fact in mid-1992.

Will they swear to such prices in a year or two?

Or $5,000-, let alone $10,000-, per-carat Paraiba stones be as much aberrations as $64,000-, 1-carat D/flaw-less diamonds? The envelope, please. All kidding aside, Paraiba prices are as close to paranormal as gem prices get. They have defied gravity, conventional wisdom and a blistering recession—an any one of which should have kept prices pinned down to the high three or low four digits. But no, prices threaten to break into the five-digit realm. That’s not just flight, that’s space travel.

Nevertheless, the strange case of Paraiba tourmaline has always been unsettling. In January 1990, when Modern Jeweler first profiled this find, it seemed prudent to treat readers as innocent bystanders in a game of chicken between dealers. After all, tourmaline then was a gem that was lucky to fetch $500 per carat at wholesale. Suddenly here was a type that was being routinely quoted to us at $1,000 per carat in relatively itsy-bitsy 2- to 3-carat sizes.

Granted, these stones were magnificent, sporting at their best electric teal and sapphire-blue colors that made them ravishingly distinctive. Nevertheless, the prices charged seemed delusional. “Asking $1,000 per carat for tourmaline is outrageous—no matter how beautiful it is,” groused New York dealer Ary Reith just when prices for Paraiba goods hit $2,000 per carat in Brazil. Reith refused to stock the gem until its prices came “down to earth.”

They never have.

Within a year, most of the dealers pledged to temperance with this tourmaline had thrown caution to the winds. And when sub-carat stones of so-so quality could command $900 per carat, ours was not to reason why, just to make whatever sense we could.

Seasoned Ticket

When dealers first saw samples of the new-find tourmalines in early 1989, the stones’ vibrant colors left them as much in awe as in doubt. “I was looking at blues and greens so electric, I just figured someone was messing with the material,” said Simon Watt, Mayer & Watt, Beverly Hills, Calif.

By “messing,” he meant, of course, irradiation. Tourmalines from Africa, as well as South and North America, are often heated or irradiated to boost color and sometimes are both irradiated and impregnated to improve appearance. Increasingly, tourmalines are both irradiated and impregnated.

Given tourmaline’s checkered past decade as far as treatment goes, stones from Paraiba were bound to trigger trade skepticism. Endowed with colors that evoked comparisons to peacock feathers and tropical fish, it is easy to understand why many importers at first passed up the opportunity to buy these newcomers.

Finally, gemologists who studied the material concluded its colors were, for the most part, natural—the product of the trace element copper. We say “for the most part” because Brazilian dealers admit heating some sapphire-blue, a well as gray and dark-green stones, to render them spectacular turquoise and tsavorite hues. No irradiation is known of or confessed to.

Once Paraiba tourmaline was given a clean bill of health, holdouts like Simon Watt began buying it. At first, its mile-high prices reflected newness and overnight celebrity status. In time, they reflected profound regard for this material. “Designers tell me that adding just one or two Paraiba melee stones to a piece for accent gives it enough extra pop to more than justify paying the very high prices asked for it,” explains Cheryl Kremkow, director of the International Colored Gemstone Association Gembureau in New York.

Starring Role

Paraiba tourmaline remains the most talked about Brazilian gem find since the 1987 discovery of that country’s richest pocket of fine alexandrite, a chrysoberyl light changes from green in sunlight to red in incandescent light. In that case, too, prices raced to levels so stratospheric—up to $8,000 per carat for relatively diminutive 2-carat sizes—that many U.S. dealers were quickly chased from the market. Yet sales still thrived for these gems because they were considered as beautiful as any known.

Curiously, supplies of both the alexandrite and tourmaline were quickly depleted. Indeed, there hasn’t been more than a trickle of new Paraiba production as miners battle over land and mineral rights in Brazil’s courts. Supposedly, these disputes were settled in the winter of 1992, but mining has yet to resume.

Meanwhile, the trade has grown more hooked on Paraiba tourmaline than any other variety of this gem in modern history. It’s easy to see why. Its blues and greens are just about the breed’s best.

Start with the blues. Except for indicolites, we have never before seen the tourmalines whose color so strongly suggests sapphire. More often than not, the best indicolites resemble London-blue irradiated topaz while Paraiba’s blues consistently beg to be likened to Sri Lankan sapphire. What’s more, stones with overtones of violet bear an uncanny closeness to tanzanite, a heated zoisite from Tanzania that has taken the jewelry world by storm.

Paraiba tourmaline excels as well with green. Indeed, the teal color of its best stones can easily summon $4,000 to $5,000 per carat in 1- to 3- carat sizes. Larger sizes, say Joe Glik of Avka Gil, New York, can cost $10,000 per carat.

It is fitting that Paraiba’s greens are this breed’s biggest money-makers. Previously, chrome tourmalines from East Africa that were tsavorite lookalikes had the distinction of being the most expensive of all tourmalines, able to bring $700 to $900 per carat if they had exemplary color, clarity and cut. By boasting unique, reverence-worthy greens, Paraiba’s stones soared to new market highs and wrote a whole new chapter in tourmaline history.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

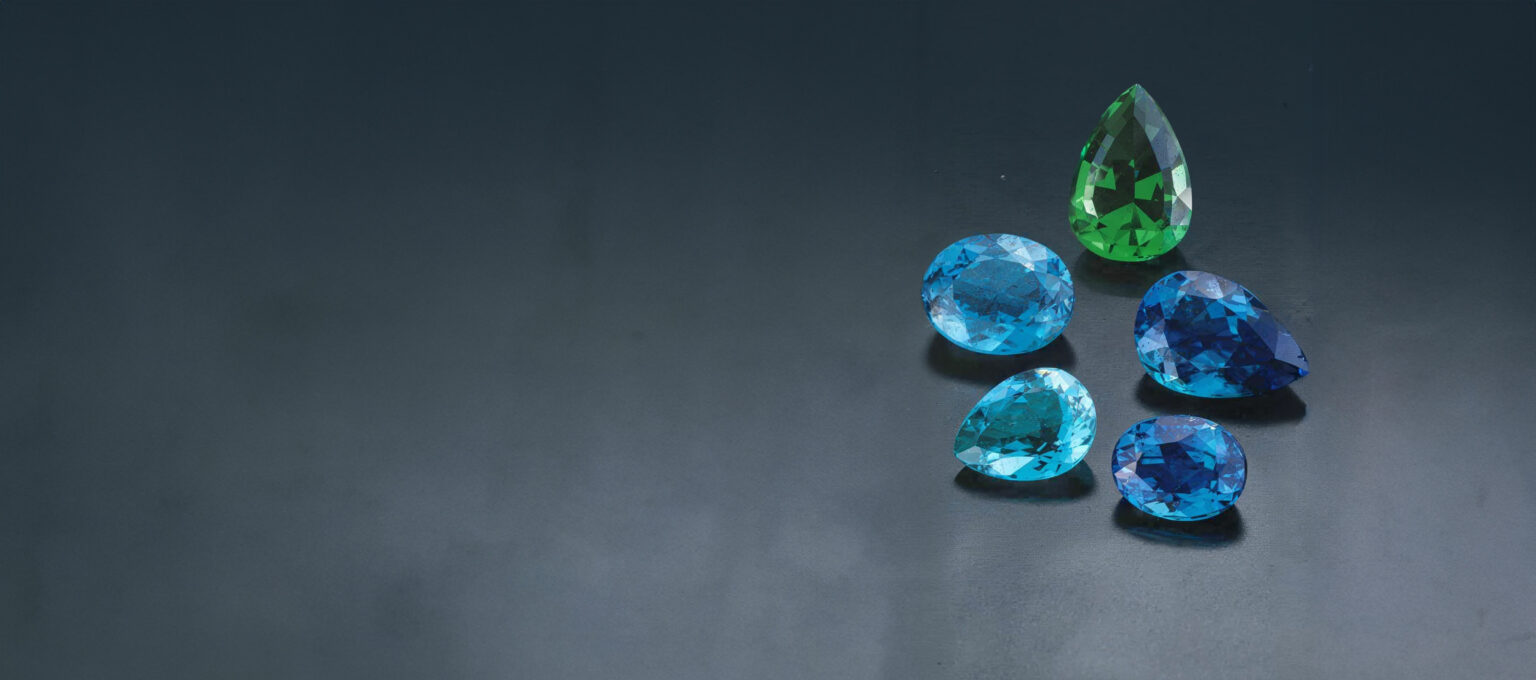

The Paraiba tourmalines shown in the header image are courtesy of Mayer & Watt, Beverly Hills, Calif. Clockwise from top, they weigh 3.12, 2.59, 1.51, 1.53 and 2.64 carats.