To most retail jewelers, opal means Australia and almost no place else. Few know that America is thought of fondly as an opal producer among gem connoisseurs. Those who know of America’s role as an opal producer may have seen some of the beautiful black opals from Virgin Valley, Nev., that collectors regard as highly as stones from Lightning Ridge, Australia.

Yet the fact that Oregon has for the past few years rivaled (some say outshone) Nevada as an opal producer is still pretty much of a secret, even in cognoscenti circles. And it isn’t because the state is a newcomer to the opal scene. Opal mining was first reported there nearly a century ago and has been going on, albeit sporadically, ever since.

Even today, production was so slim that no one took Oregon seriously—no matter how highly they regarded specimen stones. Mention isn’t even made of the state as an opal source in the latest edition (1987) of Joel Arem’s Color Encyclopedia of Gemstones, a major gem locality reference work.

Nonetheless, Oregon opal is finally starting to attract the attention of mainstream jewelers—due largely to the efforts of Vancouver, Wash., gem dealer and jewelry manufacturer, Eric Braunwart of Columbia Gem House Inc.

Up in Timber Country

Oregon opal has already captured a small but devout following among gem and mineral buffs with a taste for lapidary art. Impressive carvings by Kevin Lane Smith, a cutter, goldsmith and miner living in Tucson, Ariz., almost singlehandedly gained the first serious recognition for Oregon opal by highlighting both the gemological and aesthetic diversity of this material. The trouble was that Smith’s immense talent nearly overshadowed the importance of the material on which his reputation stood. It was as if a paint maker had hired a brilliant unknown by the name of Pablo Picasso to help it make a name for itself and the unknown made a bigger name for himself than the company. Not by design, mind you, just by dint of his genius.

Before he became as famous as he is today, Smith devoted half his life to popularizing Oregon opal. In 1987, he spent one half of his working life cutting it, the other half mining at Opal Butte in northeastern Oregon’s the Blue Mountain Range. Gradually, he focused more on cutting, less on mining. That left Dale Huett, the mine’s owner, to run things by himself until 1992 when he had to hire people to help him dig for geodes (large nodules of stone whose cavities are sometimes lined with crystals or mineral material) in which the opal is found.

Since 1987, Opal Butte production has remained constant. However, the mix of opal varieties mined changes from year to year. In 1988, for example, production of color-play stones (also called rainbow opal) was excellent. In 1991, it was poor. But in 1992, it was once again very good.

Like all opal deposits, Opal Butte produces a certain percentage of material that is prone to cracking (opal dealers call it “crazing”) as a result of dehydration. “For the most part, it is our yellows, oranges and reds that are the troublemakers,” says Huett. To ferret out unstable from stable material, some crazing-prone pieces of cuttable opal are cured by heating at 150 F for eight hours. A decrease in the number of crackups has Huett optimistic that the percentage of unstable material is declining as he digs deeper into his mountain deposit.

When Huett first started mining at Opal Butte (elevation: 4,700 feet) in 1987, digging stretched from late spring to early fall when the area is free of snow. But as sorting, selling and marketing have take a bigger bite of his time, Huett has had to cut back mining to two months a year, which is still ample time to accumulate the new inventory he needs. But it might not be if Oregon opal becomes a U.S. gemstone staple like Arizona peridot. That’s Huett’s goal. To reach it, he has signed on with Eric Braunwart’s ambitious “Gemstones of America” program.

The Dream Scheme

From time to time, when Americans are seized by a need for self-sufficiency, “Buy American” campaigns are born and thrive. In the wake of the U.S. rout of Iraq in 1991, America went from euphoric nationalism to edgy protectionism when recession set back in.

Oddly, both moods have been good for American gems. Launched after victory in the Gulf War, Columbia Gem House’s “Gemstones of America” program featured American-made mass-production jewelry with American-mined gems in calibrated sizes at very affordable prices, typically $100 to $500 retail. Counter cards and brochures made consumers aware of their own gem-mining heritage.

Although Oregon opal has figured prominently in this program, Braunwart also sells it separately. Actually, it needs specialized attention because it comes in many varieties, few of which American jewelers are used to seeing and selling.

At present, nearly 40% of the cuttable material from Opal Butte is of what is called “hyalite” opal. This is a transparent to translucent variety with a soft blue sheen, reminiscent of the milder shades of Sri Lankan moonstone, whose distinctive color Braunwart has dubbed “ghost blue.” Almost 80% of this hyalite is faceted into rounds and ovals and the remainder cut as cabochons. The cost of this material to jewelers is $20 to $50 per carat.

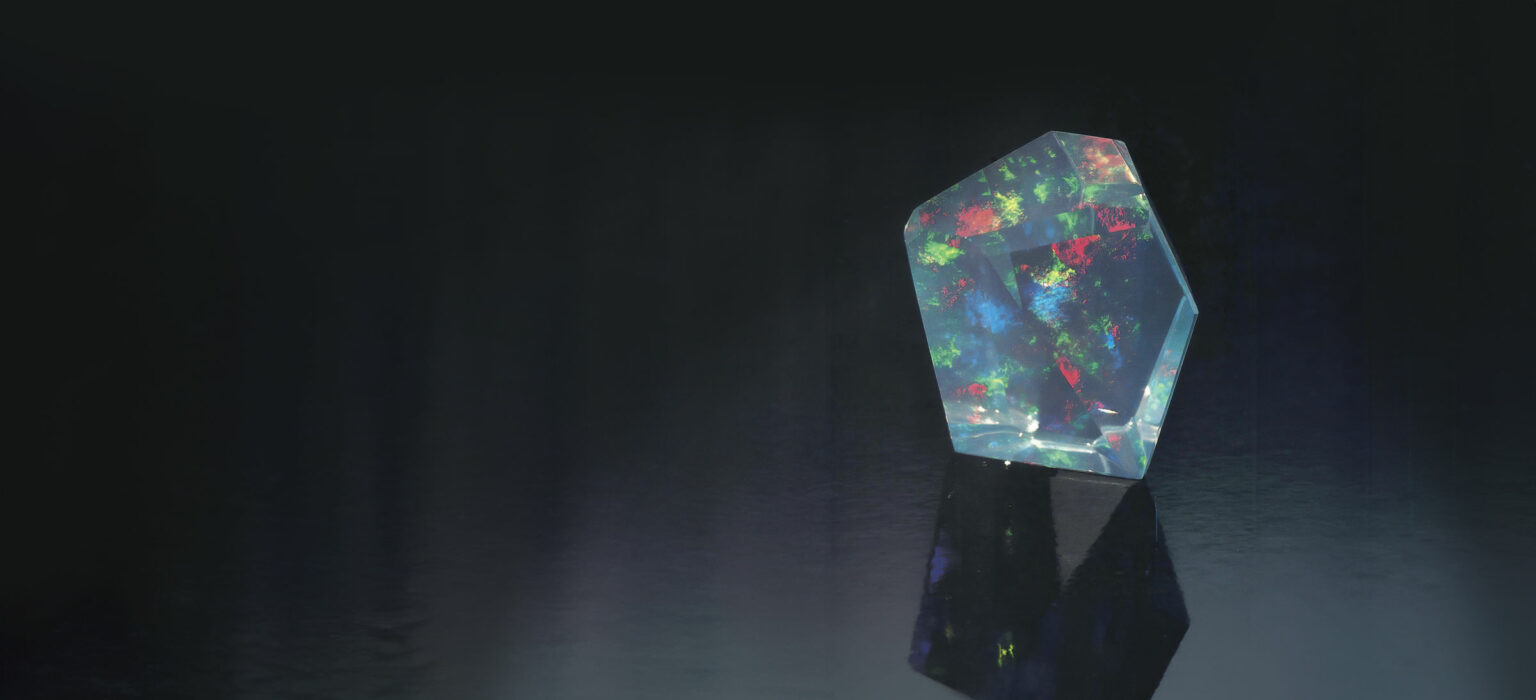

Another 30% or so of Opal Butte production is of rainbow, or color-play, opal. Unlike Australian opal, whose individual colors are usually distinguishable to some degree from one another, this opal is comprised of color particles so fine and tiny they merge and form a prismatic wash. To get some idea of the look of this opal, see the photograph of rainbow labradorite on page 76, then picture a more muted version. Of this material, most, around 80%, looks best in cabochon form, especially when cut in larger sizes to optimize color effects. The rest is faceted. Prices for color-play opal are also $20 to $50 per carat, but exceptional pieces command more.

The last variety of Opal Butte material of interest to jewelers are the yellows, oranges and reds that are similar in appearance to Mexican fire opal. Of this variety, yellows are the most abundant and reds the least. Expect to pay anywhere from $20 to $50 per carat for yellows, up to $75 per carat for oranges, and up to $150 per carat for handsome cherry reds.

For carving lovers, Opal Butte has Contra Luz opal whose holographic color-smears appear mysteriously inside otherwise transparent stones when held up to the light. These will run $40 to $125 per carat. Color-play opals with base colors such as orange can be found, in free sizes only, for $40 to $140 per carat. Top pieces fetch up to $400 per carat.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The Oregon opal shown in the header image is courtesy of Kevin Lane Smith, Seattle.