Next time you feel like cursing the IRS, think about life under Mogul rule in India. Until these Moslem nomads, descendants of the Mongols, conquered a big chunk of the country’s northern part in 1526, it was customary for potentates to tax the country’s farmers, the main source of tax revenue, at around one-sixth of their output. However, by the time the Mogul empire encompassed two-thirds of India a century and a half later, the state’s take had jumped to as much as one-half.

Such levies fattened a lot of coffers, both those of the occupiers and those of cooperating native princedoms. In fact, when one Mogul emperor ordered an inventory taken of the royal treasury, his agents gave up the task as impossible after working night and day for five months!

By now you might have guessed that the Moguls were big spenders—if not history’s biggest, then certainly among the top 10. Typical of their spare-no-expense approach to living was the Taj Mahal, built by the most lavish of all Mogul emperors, Shah Jahan (1592-1666) between 1631 and 1653 as a tomb for his wife, Mumtaz Mahal (1592-1631).

Although Jahan’s father, Jahangir (1569-1627), was a lover of opulence, his appetite for material splendor was no match for his son’s, especially in the realm of gems, the supreme acquisitive passion shared by the two. That’s saying a lot since, according to a 1622 account of Mogul court life by Edward Terry, an English chaplain assigned the East India Company trade delegation to India in 1617, Jahangir was the “greatest and richest master of precious stones that inhabiteth the whole earth.”

By this standard the scion evidently possessed enough gems to be master of the galaxy. Unlike his father, an opium addict known to love fondling women as much as precious stones, Shah Jahan seems to have put aesthetic above carnal pleasures (at least until his mid-60s when excessive use of aphrodisiacs almost killed him and set the stage for usurpation of his throne). In his chronicle of travel through Mogul India in 1640, Sebastien Manrique, an Augustinian friar from Portugal, describes a banquet at which Jahan was so entranced by stones given him as a gift that nothing—not even two near-naked dancing girls sent in as an after-dinner finale—could catch his eye.

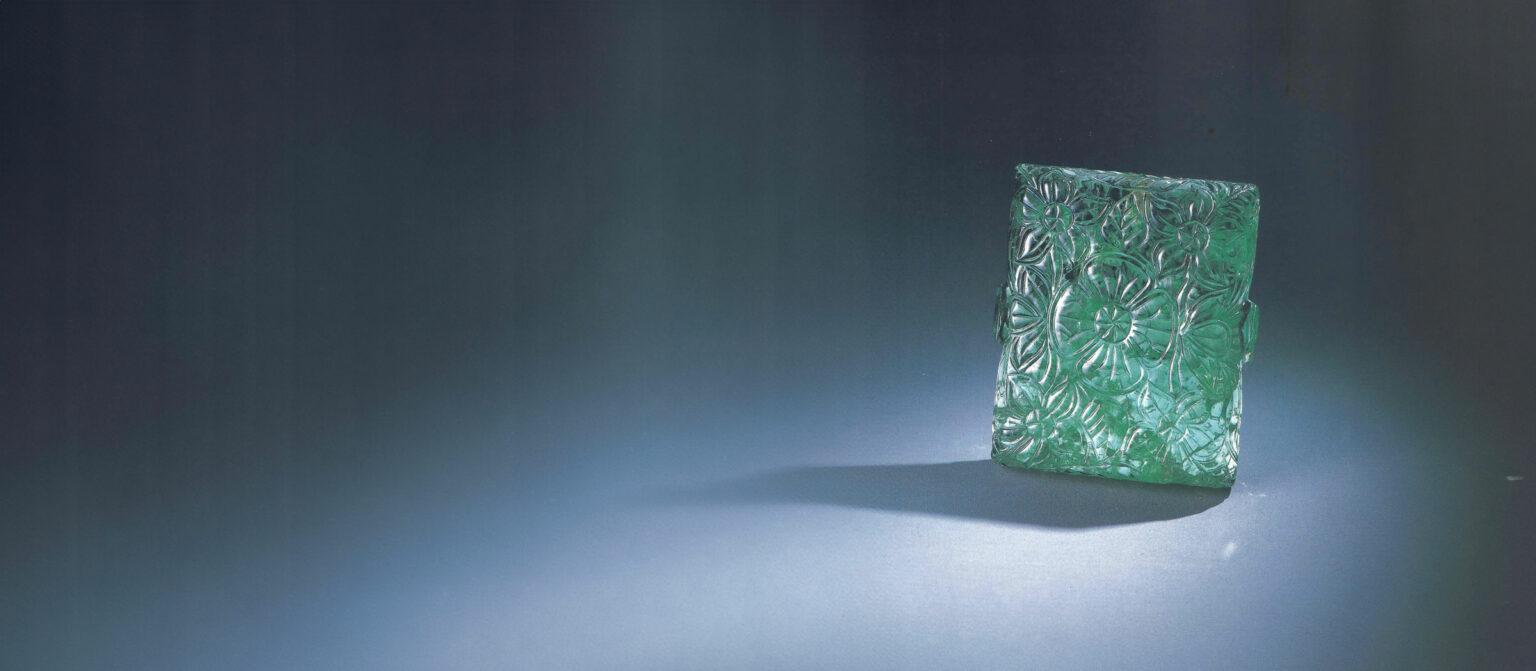

Like any connoisseur, Jahan played favorites among his gem interests, as did his son. Aurangzeb (1618-1707), who overthrew him in 1658. All of which brings us to the subject of emeralds, the gem used for a unique form of engraving, illustrated in the picture on the opposite page, which provides one of the most lasting artistic and cultural legacies of the Mogul period.

The Green of Paradise

Throughout the Koran and other early Islamic literature, the color of paradise is likened to that of emeralds—a rich, verdant green. Given such spiritual associations, fine emerald was bound to be one of the most desirable trade commodities throughout the vast stretches of the Moslem world whenever it could be found (which, prior to 1520, was mostly Egypt). No place else where more potential patrons for this berry than in Mogul India where Moslem rules reigned in luxury so prodigal that it has rarely been rivaled.

As luck would have it, Mogul ascendancy in India took place at the same time as Spanish ascendancy in South and Central America, many of whose peoples like the Aztecs and Mayans had long traded in emeralds from Colombia. By 1520, these emeralds were among the most eagerly sought booty of the conquistadors in their plunderings of Mexico, Ecuador and Peru—so much so that the Spaniards took until 1557 and 1560 respectively to discover the two main sources of these gems, the Chivor and Muzo mines in Colombia. In fact, the ill-fated Spanish galleon called the Atocha that sank off the Florida Keys in 1622 and was found in 1985 contained a significant number of uncut Colombian stones. Had the ship escaped disaster, it is very likely that the best roughs on board would have been sent to the Philippines, then transshipped to India where emerald-smitten Mogul monarchs could be expected to pay prices far greater than their European royal counterparts.

As was by then tradition in Islamic countries, many of these emeralds were inscribed, for essentially religious purposes, with floral motifs and Koranic texts or both. This practice was most pronounced in Mogul India during the reigns of Shah Jahan (reigned 1628-1658) and Aurangzeb (reigned 1658-1707). Although stones such as spinel and turquoise were also common candidates for inscribing, emerald was probably the first choice, especially since it was available in unprecedented abundance from America.

Unappreciated Art Works

No one knows how many Colombian emeralds were engraved in the royal workshops of Mogul India. Many of these stones wound up in the private treasuries of Hindu rajahs, Jain princes and Moslem sultans as the Mogul empire began to crumble in the 18th century and its riches were traded, sold or stolen.

Then when India gained its independence from Britain in 1947, many local rulers lost the power to tax their subjects. To keep their extravagant lifestyles going, many of India’s titled elite put some of their finest Mogul emeralds on the market for sale. Unfortunately, most of the gem dealers to whom these inscribed emeralds were offered had little or no understanding of their historic or aesthetic value. Rather, they regarded them as pieces of rough and bid for them based on their estimated yields of cut stones. Such insensitivity may be responsible for the destruction of hundreds of Mogul emeralds. “It is only in the last 10 years,” says Islamic jewelry expert Derek Content, “that these pieces have been appreciated for what they are.”

Now considered among the most regal relics of Moslem and Indian history, fine Mogul emeralds can increasingly command hundreds of thousands of dollars as connoisseurs worldwide vie for ownership of them. In 1989, for instance, a Cartier brooch made in 1930 for the late Agha Khan III that featured a 142.40-carat Mogul emerald fetched $613,000 at a Christie’s sale in Geneva.

As Western interest in Islamic culture increases, competition for Mogul emeralds will no doubt intensify, forcing prices for the few pieces that become available to even higher levels. Given the hundreds of art and natural history museums in America alone that might feel obliged to have a Mogul emerald on permanent exhibition should fascination with Islam continue, current prices for these rarities may soon seem like bargains.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The Mogul emerald shown in the header image is courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History, New York.