No fancy color diamond collection is complete without a green stone. But since, next to red, green is probably the rarest of all natural diamond hues, most collections lack representation from the green portion of the diamond rainbow. Even when they do contain greens, the stones’ color is usually not a bona fide natural one—or at least not classified as such by a gem lab of stature.

Needless to say, this is a rather frustrating situation for connoisseurs. And it arises out of the highly ironic fact that green, while among the rarest of natural diamond colors, is the commonest of artificial ones—easily induced by alpha, electron, gamma and neutron irradiation. Yet connoisseurs spurn stones with lab-contrived color, instead dreaming of some day owning a green diamond with incontestably natural color.

As things stand, that’s dreaming a nearly impossible dream. Since 1985, only a very few diamonds with color certified as being of natural origin have been sold at auction. Two of the most notable: a 51-point dark green sold for $69,000 per carat at Christie’s in December 1985 and a3.02-carat “apple-green” sold for $568,000 per carat at Sotheby’s in April 1988.

In the past, labs were loath to validate green in diamonds as natural unless stones showed what was once thought to be a telltale indicator of natural color origin: tiny circular green and/or brown stains seen with magnification on the unpolished surfaces, called naturals, of finished stones. For instance, the 3.02-carat stone just referred to had such stains (in a girdle fracture) and was accompanied by an April 1985 GIA report with the following comment: “Color and characteristics of this stone suggest natural color.”

Today, however, the same evidence of natural color origin would probably not be enough to merit a green diamond a comment this affirmative from GIA. Diamond graders there say that about the best such a stone can hope for at present from the school’s trade labs is to have its color origin classified as “undetermined.” While such wording may smack of fence-sitting, it is understandable since GIA feels that definitive proof—not merely educated opinion—is expected of it when making complicated color origin calls.

Definitive proof may be years away. In its absence, colored diamond experts think that both the gemological and connoisseur worlds must learn to live with educated opinion.

It Isn’t Easy Being Green

Unlike other natural colored diamonds, the cause of color in green stones is thought to result from natural irradiation in the earth—most likely after the stones’ formation. According to current diamond color theory, some time in a diamond’s history it comes into contact with a mineral (e.g., pitchblende) containing radioactive elements such as uranium whose high-energy particles create defects in the stone’s atomic structure.

These radiation-induced defects are, in turn, responsible for the absorption of wavelengths of red light by the diamond that result in the transmission of a complementary green color to the eye. During an examination of Germany’s famous 41-carat-plus Dresden diamond—to natural green diamonds what the Hope diamond is to natural blues—a team of three gemologists found that spectroscopic analysis of the diamond confirmed this explanation of green diamond color chemistry.

Lab-greening of diamonds by irradiation was first performed by Sir William Crookes in 1904 when he packed convention-al diamonds in radium bromide salts for a year or so. These experimental stones remain radioactive to this day and thus cannot be worn. It took until 1942 to green diamonds safely, using a cyclotron to accelerate high-energy particles. By the 1960s, diamond greening was done with streams of electrons in linear accelerators and neutron bombardment in a nuclear reactor.

Irradiation (coupled with heating) can produce colors such as yellow and brown that often look identical to hues produced by nature. Fortunately, these treated colors betray their lab origins by showing absorption lines that are uncharacteristic of stones with natural colors. The reason for the different spectroscope readings between other-than-green natural and treated diamonds is their different color genesis. Excepting green, natural color stems from entrapment of impurity atoms (usually nitrogen) or crystal lattice damage during the creation process, while treated color results from irradiation and subsequent heating after a diamond is formed.

On the other hand, nearly all green diamonds—natural or treated—owe their color to irradiation (and, to a lesser extent, fluorescence). So whether stones are colored in the earth or in, say, a gamma cell, they will often show the same wavelength absorption lines. This doesn’t mean that experts can’t ever tell apart lab- from ground-greened diamonds. But even when they can, the job is never easy. Gemologist Stephen Hofer of Colored Diamond Laboratory Services, Miami, envisions development of simple, effective color origin tests using “radioactivity dating techniques to determine when stones were irradiated.”

The Dream Goes On

Given the difficulty of authenticating a green diamond’s color as natural, many dealers long for times when, based on a few signs or even gut instinct, a green diamond could be presumed natural. Such a longing can lead to trouble.

In 1990, a limited number of rough and cut diamonds with pale green colors began to surface in the United States. Colored-diamond dealers jumped at the opportunity to buy these light and lively stones with hues vastly different from the comparatively somber shades of conventional irradiated diamonds. “They were being offered as natural by people with impeccable credentials,” says Alan Bronstein, Aurora Gems Inc., New York.

From the first, seasoned gemologists were skeptical about these pistachio-green diamonds. “While the color of these stones seems natural, their physical characteristics are not consistent with what researchers think of as natural green color,” Hofer explains. Particularly disturbing: brown irradiation stains on naturals that seemed far too weak in comparison to the uniform pale-green body color of the stones.

De Beers’ own Diamond Research Center, Maidenhead, England, reached the same conclusion about these gems. “When you have a large number of stones of different origins and morphology but all the same hue, you have to suspect that they were treated en masse,” says Martin Cooper, director of Research and Development.

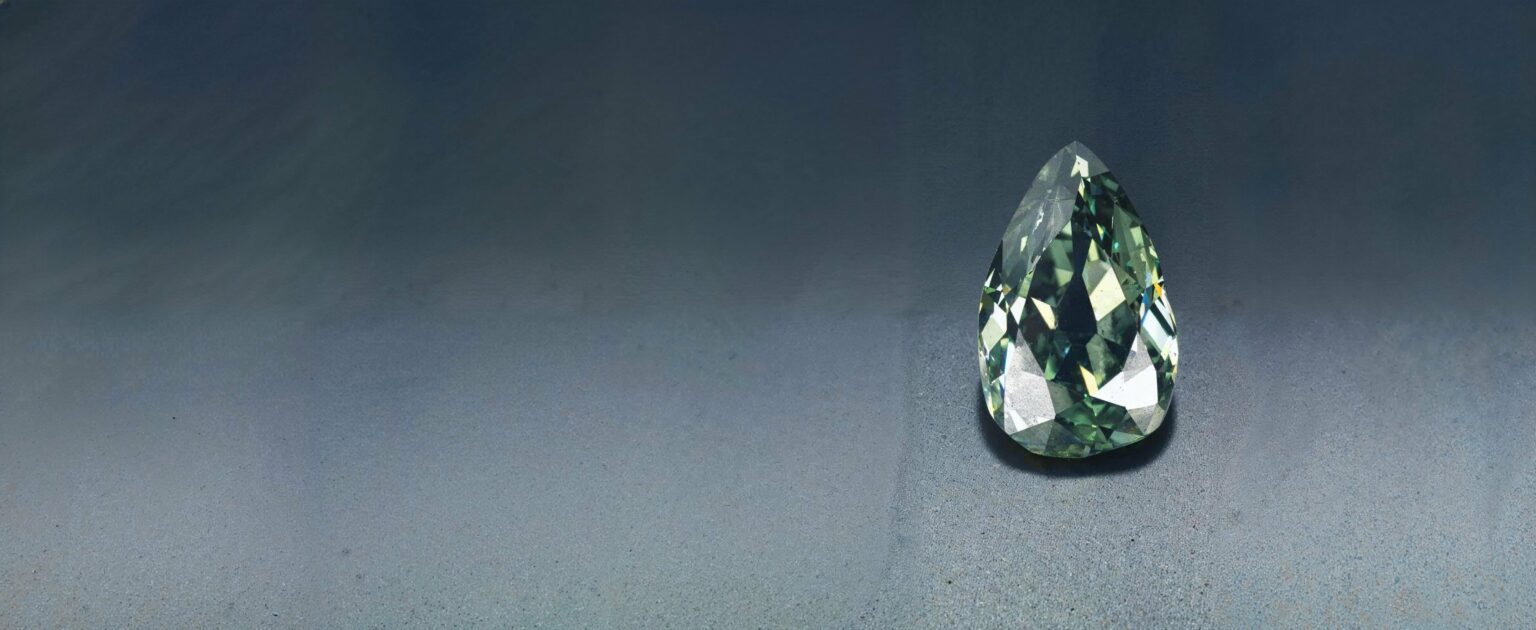

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The .62-carat green diamond shown in the header is courtesy of Aurora Gems, New York.