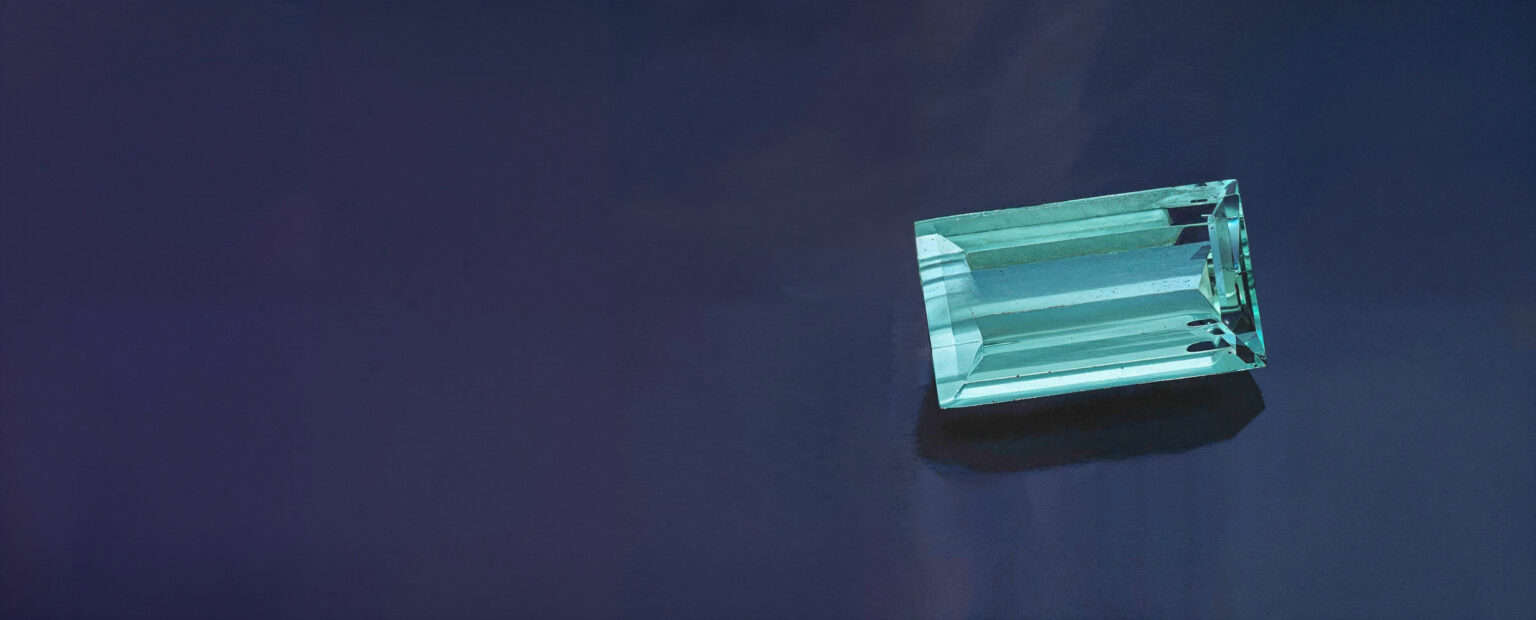

The owner of the luscious green beryl you see on the page opposite had every right in the world to sell it as emerald. It’s got chromium, the coloring agent of emerald, and that’s all this stone needs nowadays to be certified as such by European and Asian gem labs. In America, where the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) uses visual, as opposed to chemical criteria to distinguish between green beryl and emerald, the stone must reach certain tone and saturation levels to be called the latter. But even by GIA standards, this stone can be called “emerald.”

Yet Joe Gill, of Akiva Gil, New York, sold it as a green beryl. “Calling the stone ‘green beryl’ enhanced its value because fine green beryl it’s so much rarer than emerald,” he explains. “Big deal,” says a fellow dealer. “Selling an emerald as green beryl makes about as much sense as selling a ruby as red corundum.”

To most colored stone dealers, the name “green beryl” is little more than a euphemism for bad emerald and aquamarine, both members of the beryl family. And it is has long been so.

Equating green beryl with mediocrity became standard practice in the early 1980s when the jewelry industry battled mail-order marketers of dull and cloudy $5 emerald. But green beryl’s reputation was in tatters long before this. From the time that German dealers learned how to heat bluish-green Brazilian beryls to rid them of green and leave them a lovely ocean-blue, stones that proved irremediable were looked on as failed aquamarines.

The trouble with these negative notions about green beryl is that they are wrong—decidedly so. Nevertheless, it took a mid-1980s find of aqua in Nigeria to show the industry how foolish it was to let the name “green beryl” become a double-duty alias for low-grade emerald and aqua. At the same time, the discovery forced the trade to face the sharp clash between its disregard and earlier regard for green beryl.

Romance vs. Reality

Until this century, the vast majority of gems the world thought of as aquamarine were green beryls. Indeed, the term “aqua” was a wide berth one that conjured a diverse range of sea-water tints from blue to bluish-green to greenish-blue to green. While true-blue beryls were highly prized, these stones were so rare that the presence of secondary green was not considered a drawback.

Then, around the turn of the century, German dealers made a momentous discovery: heating green-blue Brazilian beryl to 400 C permanently changed the state of its coloring agent, iron, and eliminated all traces of green in the process. Voila, pastel-blue aquamarine as we know it! Almost overnight, the term “aquamarine” became synonymous with blue, and blue alone, in the gem world. In a matter of decades, the public expected all aquamarines to be blue and had little tolerance for greenish ones.

As long as material from new deposits of green beryl could be heat-treated blue, the trade did not have to worry about rekindling affection for greenish-blue aquamarine. Eventually, however, a major discovery of aquamarine in Nigeria around 1983 threw dealers into this very quandary. Because this beryl contained chromium, along with iron, its green proved colorfast—even when subjected to oven heating.

Unable to change the stone’s color, dealers sought to change its name. Thus this Nigerian beryl became the center of one of the fiercest Euro-American gemological controversies in decades: deciding when a green beryl is or isn’t emerald. European labs, backed by the International Confederation of Jewelry, Silverware, Diamonds, Pearls and Stones (CIBJO), insisted emerald is defined solely by its chemical composition. GIA said the cut-off between emerald and beryl should be based on appearance factors.

But knowledgeable collectors didn’t seem to care what the beautiful beryls from Nigeria were called. Once the deposit ran dry in 1991, superb stones soared to as much as $1,000 per carat in 5- to 10-carat sizes while lovely stones in 3- to 5-carat sizes hit $400 per carat.

All of the Nigerian green beryls that we have seen recently were cut in Israel, many of whose emerald dealers have diversified into aquamarine, most of it from various African localities. However, fine green beryls are also being cut in Idar-Oberstein, Germany. Dealers in both places say top-notch green beryls should be flawless and well proportioned.

But With Nigeria temporarily out of the rankings as a source of green beryl, Brazil and Madagascar are counted on for the scant supply available.

Prior Passion

Modern attitudes towards green beryl (or greenish aqua) would baffle our forerunners. Gem scholars can make a pretty convincing case that the ancients held greenish aqua and its brother beryl, emerald, jointly in high esteem. Just how far back this esteem runs is a matter of debate.

Most likely the first source for green beryl was India. Historians have conjectured that its discovery there took place anywhere from 1500 B.C. to 400 B.C.

Interestingly, recent efforts find a spot aqua and emerald in a part of Afghanistan corresponding to an ancient southwest Asian country, known as Bactria by prove this area was an early source of both aqua and emerald. Certainly the find confirms references to this source found in “Natural History,” that monumental catalog of natural phenomena written by Pliny the Elder circa 50 A.D. In his treatise, Pliny rated Bactrian as the world’s second-best source of emerald (with Egypt first). Since in Pliny’s time, emerald (then smaragdus from the Sanskrit word for “green”) was used interchangeably for aqua, emerald and at least 10 other stones he called by that name, no one never really knows what Pliny had in mind.

Nevertheless, there seems to have been some awareness in ages past that emerald and green beryl were not quite the same. Despite Pliny’s blanket use of the term “emerald,” a distinction of sorts was drawn by some authorities between the two. We see it at work in descriptions of the famous breastplate made for Aaron, Moses’ brother and Israel’s first high priest, circa 1550 B.C.

This vestment, which is first described in Exodus, had 12 gems arranged in four rows, three to a row. In successive versions of the Old Testament, stones three and four were at different times believed to be emerald while stone 11 was at times believed to be beryl. There’s a lesson there for us moderns about prizing green beryl.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 6.86-carat green beryl shown in the header image is courtesy of Akiva Gil Co. Inc., New York.