There are two distinct cultures in the world of colored stone retailing—the jewelry store and the rock shop. Rarely do they converge, although there have been crossovers from one to the other—usually from the rock shop to the jewelry store world and almost never the other way around.

Each of these cultures has gems that are associated with it. Rock shops, with their large collector/hobbyist clienteles, are identified with gems traditionally labeled “ornamental” because they’re non-facetable, exotic-looking and inexpensive. A few of these so-called ornamental stones like malachite and rhodochrosite have earned small, mostly token niches in mainstream jewelry stores.

But a lot more of these rock shop exclusives merit serious attention from jewelers, preferably ones with enough design savvy to know how to sell customers on the idea of buying off-the-beaten-track stones.

If you’re such a jeweler and you’re looking for a men’s phenomenon stone to set you apart from the competition, we call your attention to fire agate, a chalcedony that at its best rivals top opal for mysterious color play—at a fraction of top opal’s cost. “It amazes me that this gem has never found a wider audience as an opal substitute,” says Ray Zajicek, Equatorian Imports Inc., Dallas.

That time might be now, given the scarcity and expense of both fine black and white opal, plus a noticeable fall from favor of fire agate in the rock shop world.

Limited History

It has not been easy to light a lasting fire, in terms of public interest, for fire agate. No major gemologist or gem scholar has, to our knowledge, championed this stone. To the contrary, most have been mum, or nearly so, on the subject. For starters, fire agate isn’t even mentioned in Max Bauer’s 1896 masterpiece, “Precious Stones.” And it receives only five lines in the most widely acclaimed modern survey of gemology, Robert Webster’s “Gems.”

Bauer can possibly be excused for his oversight since the stone may not have yet been discovered when the German put his eloquent pen to paper. Lapidary Bruce Iden, Boulder, Colo., thinks fire agate is a post-World War II find. “I don’t remember hearing about it much before 1960, when lots of rough started coming out of Mexico,” he recalls.

Shortly thereafter, smaller deposits were reported in Arizona and New Mexico. “Given the fact that it is mined only in the Southwest, it caught on basically as a regional item for men,” says Zajicek, who still has most of a 300-pound lot of fire agate rough he bought on speculation 15 years ago. “I’ve waited a long time for the stone to make a bigger splash, but it never has.”

If anything, fire agate’s appeal as a Southwestern men’s gem has fizzled in recent years. “The stone needs a new marketing angle if there’s going to be a comeback,” Zajicek says. For Zajicek, the angle to pursue is as an American continent opal substitute. “Fire agate has got the beauty of opal, with better hardness and durability, at far less cost.”

Unfortunately, the gem also has problems that discourage use by all but the most resourceful jewelers.

Following the Layers

Fire agate owes its shimmering brilliance and shifting colors to inner layers which have been thinly coated with an extremely iridescent material called “limonite.” In fine pieces, this iridescent layering is continuous throughout. More often, however, it runs in patches or when sustained is weak.

All of this makes cutting fire agate one of the less enviable lapidary tasks. “It is a very difficult stone to cut,” says Loreen Haas, Crown Gems, Sherman Oaks, Calif. “You have to adhere to the curvature of the color layerings, which severely limits the number of cabochons you can make.”

Instead, cutters must go with the flow of the stone, “carving more than cutting it,” notes Inden.

The end-result is an abundance of curvy, asymmetrical shapes suitable for custom crafting, not mass production. This lack of calibrated sizes has been the single greatest bar to jewelry-maker discovery and use of this chalcedony. Indeed, the vast number of free-form fire agates constitutes one of the gem world’s least publicized stockpiles and explains fire agate’s attractively low prices. The highest price quoted to us by regular U.S. suppliers of this stone was $20 per carat for large, superb (40-carat pieces, the type that have been finding their way into somewhat extravagant bola ties for at least 15 years. More frequently, however, the cost to jewelers will be a couple of dollars per piece.

At such prices, fire agate demands some attention from retail jewelers, but obviously ones trained in jewelry arts. Few of these stones lend themselves to conventional mountings. Haas recently designed a combination fire agate and accent diamond piece, “totally one of a kind,” for a customer, and Iden made two fire agate pendants.

The Palette of Fire

Descriptions of fire agate sound as if they were drawn from centuries of opal aesthetics. Dealers talk of color play in terms of “broad flash” and “pin fire,” rating its beauty as if they were evaluating fine opal.

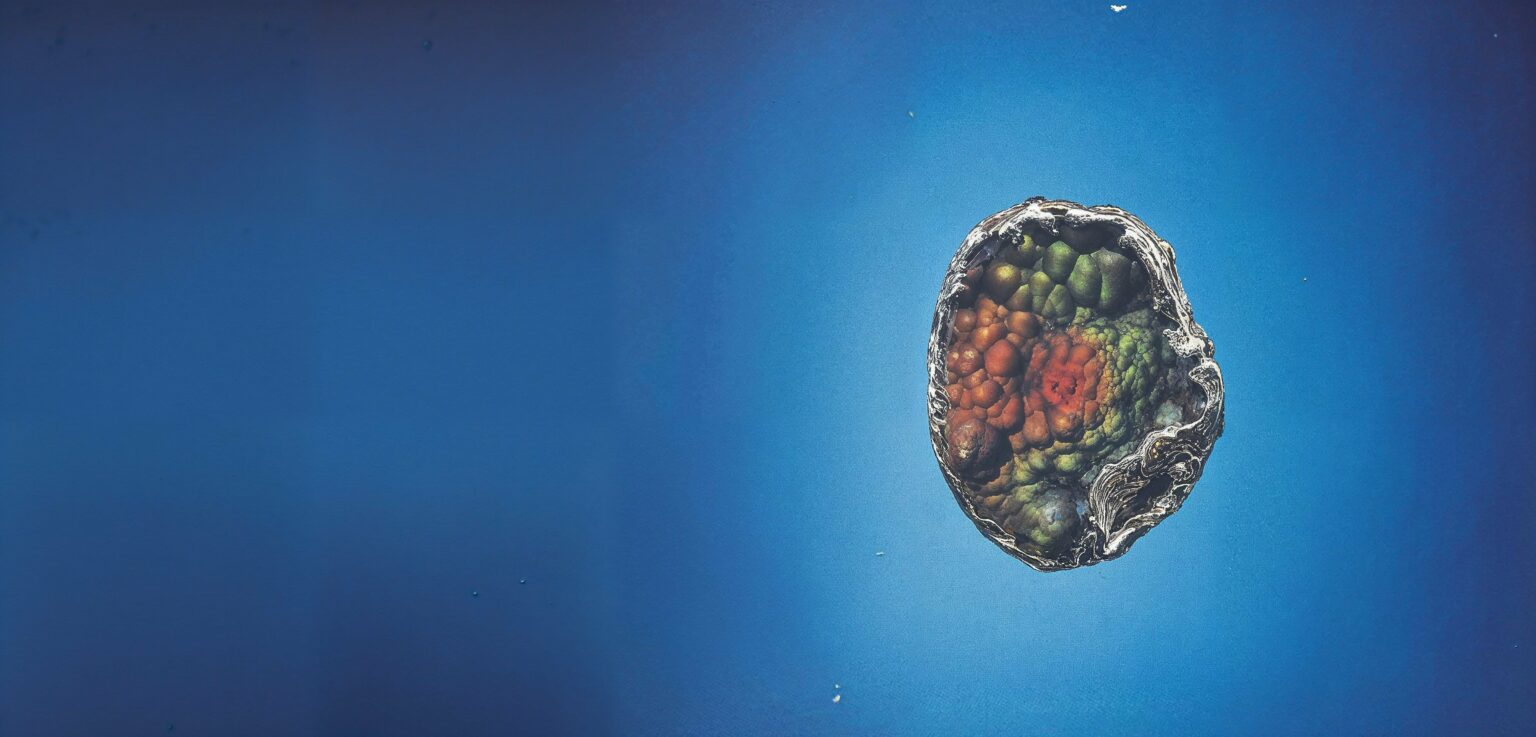

At its best, fire agate has ember-like flashes of red and orange that seem to glow in a manner reminiscent of white-hot coals. The experience of seeing such a stone is, in our opinion, unforgettable and explains at a glance the magnetism of fire agate for men.

Not all fine fire agates resemble burning coals, however. Strong mixtures of blue and green are also very desirable. Indeed, fire agate says strong blue is the most sought-after color in fire agate after red. The least desirable color, everyone agrees, is brown.

Besides color play, color pattern is important. We’ve heard fire agate’s color patterns described variously as resembling “lizard skin” and “raw brains.” In any case, the color pattern should be well-defined and even throughout the stone.

Finding ideal fire agate with full color play running across the stone, in usable shapes especially, is a bit of a chore these days. Most standard stone dealers don’t even stock this stone. And the few who do may be sitting with the dregs of a once far bigger inventory. Consequently, most stones jewelers will see are likely to be marred by excessive brown, their areas of color play rather dull or dowdy. Gemologist Charlotte Crosby, a stone buyer for Lucien L. Stern Inc., New York, re-cently returned a shipment of such fire agates sent her from Idar-Oberstein priced at a breathtaking $25 per carat. “The stones looked like boomerangs and possessed little fire to boot,” she complains. “They were of no use whatsoever.”

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The fire agate shown in the header image was courtesy of David Penney.