Until a year or so ago, having exclusive distribution rights for the world’s largest chrysocolla quartz mine would have been an oddball distinction, of interest perhaps to late-night and game-show hosts looking for yuks. But with blue and green chalcedonies suddenly among the hottest rocks in custom design jewelry, this claim is no longer a laughing matter.

To the contrary, it’s bringing serious attention to Michael Randall, Crystal Reflections, San Anselmo, Calif., marketer for a four-year-old mine in Mexico that he predicts by the end of 1992 will become the most productive source ever of what he calls “gem silica chrysocolla” and whose location, consequently, he keeps top secret.

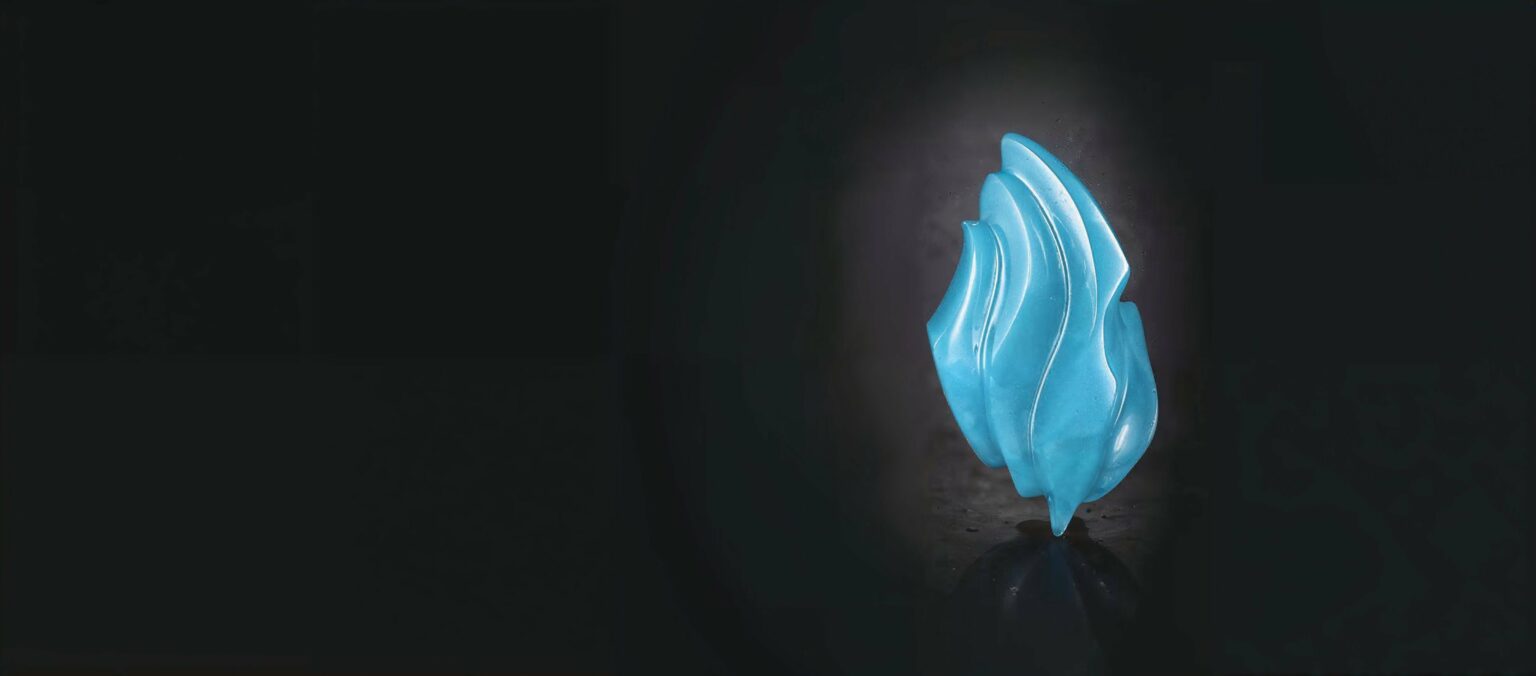

At its best, this Mexican quartz boasts sky- and turquoise-blue color, plus remarkable translucency. These traits have endeared the material to top U.S. gem sculptors like Glenn Lehrer and Michael Dyber whose works, regularly on display at gem and mineral shows across the country, have, in turn, begun to attract artisan jewelers to the material, mostly in cabochon form. Randall, himself a lapidary and designer, is using these cabochons as center stones in pieces that retail for between $350 and $1,400 without diamonds and for $800 to $2,200 with them.

Given the gem world’s heavy reliance on Randall at present, cabochons of his chrysocolla are far more expensive than other popular chalcedonies such as the violetish, at times adularescent, blue chalcedony from California (called Mojave Blue) and Africa, as well as apple- to jade-green chrysoprase from Australia. While these stones are readily available to jewelers for $10 per carat and less, the finest pure-blue Mexican chrysocolla are netting the $50-per-carat marks.

Besides reflecting Randall’s enviable grip on supplies of rough, current prices for gem silica chrysocolla stem from factors unique to this gem. To understand them, you’ll need a primer on chalcedony in general and chrysocolla in particular.

With or Without Quartz

Chalcedony is a member of the quartz family, the most common and varied of all minerals. Gemologists divide quartz into two groups: “crystalline,” which includes the transparent and facetable kinds like amethyst and citrine, and “crypto-crystalline,” which includes the ornamental and rock-like kinds such as agate and onyx. By “crystalline,” gemologists mean a material that is formed in one distinct crystal. By “crypto,” or “micro-crystalline,” they mean, as John Sinkankas writes in “Gems of North America,” “masses composed of billions of exceedingly minute crystals, too small to see clearly even under strong magnification.”

In general, crypto-crystalline quartzes are classified as chalcedonies or agates—the former usually comprises of stones with one homogeneous color, the latter of stones with patterns.

Unlike crystalline quartzes colored by minute concentrations of trace elements, chalcedonies, which are dull and milky gray in their colorless forms, are stained during their formation by infiltration of solutions carrying different metallic salts.

In most cases, chalcedonies owe their color to iron oxides. For instance, other compounds may do the coloring. oxides. For instance, quartzes stained apple- to jadeite-green due to the absorption of nickel silicate are called “chrysoprase.” Those imbued with shades of greenish and pure blue by the leaching of copper silicate are known by at least three names: “quartz chrysocolla,” “chrysocolla chalcedony” and the newest, coined by the late Paul Desautels in 1964, “gem silica chrysocolla.”

But never say “chrysocolla” alone.

The name “chrysocolla” by itself refers to a hydrous copper silicate of varying composition, the most famous variety of which is called the “Eilat stone,” a copper mineral hodge-podge which includes chrysocolla and turquoise. Considered a turquoise look-alike, this stone derives its name from its origin spot near Eilat at the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea.

While often attractive in color, chrysocolla that has not been infused with quartz has a debilitating hardness of 2 to 4 on the Mohs scale, disqualifying it for general jewelry use because of extreme brittleness. Yet combine copper silicate with quartz, as nature does with gem silica chrysocolla, and the resulting aggregate jumps in hardness to 7, making the silicated variety far more suited for cutting and wearing.

In Short Supply

Although quartz has a reputation for abundance, gem silica chrysocolla is relatively rare—at least by quartz family standards. Most modern occurrences have been found in copper deposits throughout the American Southwest, including Nevada, New Mexico and Arizona.

One of the first major finds of the material in America dates from 1907 at the Keystone Copper Mine, a few miles west of Globe, Ariz. Subsequent discoveries were made at the Live Oak Mine, also near Globe, and the Inspiration Mine, near Miami, Ariz. It is worth noting that early marketers of this quartz called it “blue chrysoprase.” Right Church, wrong pew.

Although deposits of quartz chrysocolla have never been numerous, supply was for decades more than adequate to meet sparse demand. Then around 1960, a find in Taiwan (now exhausted) triggered strong Asian demand, quickly depleting American backlogs of this material. “It was thought to resemble blue jade,” Randall says, “but gem silica chrysocolla has a far more vivid blue.” When it’s blue, that is.

Far more often than not, gem silica chrysocolla is primarily or strongly green, similar to some varieties of turquoise. But while it can match the finest turquoise for blue, this chalcedony has one attribute not found in the sky-blue gem to which it is likened: a glowing translucence that has sparked sizable overnight demand for this quartz in the Far East. “Half my orders now come from Taiwan, Hong Kong and Bangkok,” says Randall.

Ideally, gem silica chrysocolla should possess a turquoise blue that is even and highly translucent, although enthusiasts who want this gem mainly for color tolerate pure-blue stones that are opaque. Blue stones with homogeneous color and high translucency can command up to $50 per carat at wholesale today. If you just want fine color and don’t mind opaque stones, prices will be around 30% to 40% less. On the other hand, if you want translucency and don’t mind a blend of green and blue, the price will be 50% to 60% less. Ranging from $8 to $15 per carat, stones that are almost entirely green are the biggest bargains.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 27.3-carat chrysocolla quartz shown in the header image is courtesy of Crystal Reflections, San Anselmo, Calif.