Connoisseurs may glorify rare Kashmir sapphire with its soft velvety blue. Collectors may extol the hard-to-find Burma breed with its crisp royal color. And specialists in swank gems may laud the Sri Lankan variety for its cool, stately hues.

But no one sings the praises of Australian sapphire, even though it was about the only variety known to the common man for nearly 30 years until Thai sapphire supplanted it as a market mainstay. Now it is unlikely anyone ever will.

For Australia’s claim to fame was in the realm of quantity. Indeed, it was to bulk what Kashmir was to beauty. Since the early 1960s, it had enjoyed unrivaled leadership as a sapphire producer. Then between 1985 and 1991, it went from supplying 60% of the world’s sapphire to around 20%. That killed Australia’s reputation as a key source of bread-and-butter stones. Even when it was, dealers disliked its dark-toned, slightly greenish-colored goods.

Strangely, the inkiness that made this corundum a bane to aesthetes made it a boon to mass manufacturers and marketers. As late as 1989, Benny Hakimi of Intercolor in New York told us, dealers assumed that any mass-produced piece of sapphire jewelry used Australian material. “It was the only reliable source of matchable goods for decades,” he said.

Because America was the world’s chief manufacturing center for mass-production jewelry, the vast majority of Australia’s blue sapphires wound up here. But as chain stores became a bigger factor in Europe and as new markets for low-end jewelry emerged in the Pacific Rim area, exploding demand for inexpensive sapphire suited to mass production drove up prices for all but the lowest-grade Australian goods at least 50% in just two years.

Spiraling prices prompted exploration for sapphire in Thailand, long a producer of the gem. And since the Thais bought 90% of Australia’s production, success with mining at home was sure to hurt sales in Australia. Matters weren’t helped by the fact that Australian sapphire resisted oven touch ups.

Heat to the Rescue

Ever since meaningful sapphire production began in Australia around 1890, the Australians’ role in the success of their corundum has been restricted almost exclusively to mining it. Distribution has always been handled by people as strongly versed in gem enhancement as they are in cutting.

Peripatetic dealers from Idar-Oberstein, Germany’s centuries-old cutting center, were the first market-makers for Australian sapphire. They bought the lion’s share of rough found at the Anakie alluvial fields in central Queensland (Australia’s most significant deposit until 1959 when large-scale mechanized mining began at the New England fields of northern New South Wales), processed it back home, then sold the finished goods to Czarist Russia. World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917 ended Australian sapphire’s initial period of popularity.

Part of that processing may very well have included some form of heat treatment. How else could the Germans have succeeded with Australian sapphire given the gem trade’s then somewhat low esteem for this material? In 1908, gemologist Max Bauer wrote rather unflatteringly that “Australian sapphires, as a rule, are too dark to be of much value as gems.” Very likely the Germans were quietly broadening the new sapphire’s appeal the way they had broadened the appeal of Brazilian aquamarine—namely, by heat-treating stones to improve color.

Certainly, oven alchemy is the key to Australian sapphire’s second and far greater wave of popularity in our time. Using this rehabilitation method to lighten up goods, Chinese dealers from Thailand, the main buyers of Australian sapphire from 1960 on, were able to justify massive purchases of what otherwise would have been mostly unusable rough. For more than 20 years, 10 or so Chinese firms were buying an estimated 90% of the output direct from Australia’s fields.

That the Thais were heating Australian sapphires in the 1960s to make them salable seems to have escaped trade notice. But it must be assumed that they were doing so because it is generally conceded that this material has little or no commercial value if deprived of heat treatment. Evidently, however, Thai adeptness with heat has grown increasingly sophisticated during the few decades they have spent mastering its intricacies.

Heat is necessary for the market preparation of Australian sapphire in order to dissolve the heavy silk that is a major internal characteristic. Unless this silk is removed, Australian sapphires tend to be plagued by pronounced blue/greenish-blue dichroism (transmission of two different colors when a gem is viewed in different directions) that impacts on objectionable greenish cast to stones. From the look of recent purportedly Australian sapphires we’ve seen, the heat treaters of Bangkok have become quite expert at minimizing annoying green. Of course, there is the strong possibility these stones are, in reality, of Thai origin.

The High Cost of Cheap

During the early 1980s, when the world jewelry market was in the throes of recession, output at Australia’s New England fields began to decline as sapphire prices dropped and mining expenses rose. But as long as the U.S. dollar was strong, this situation posed no problem for American stone importers because they could outbid both established European and nascent Asian dealer competition for dwindling supplies. In 1985, however, when the dollar began its sharp three-year plunge against the Japanese yen, Swiss franc and German mark, Americans gradually started to find the cost of maintaining Australian sapphire climbing uncomfortably high as exchange rates turned against them.

To make matters worse, Thailand had become as much a jewelry manufacturing as a gem-cutting center, providing low-cost mass-produced jewelry to markets everywhere. Thai jewelry firms could afford to pay more for Australian sapphire since its higher cost (usually way under $100 per carat for popular sub-carat sizes and round, oval and pear shapes) was more than offset by labor costs that were a fraction of those in America.

But as Thai manufacturers improved the quality of their lines, they sought better-grade goods in massive quantities. Overnight, backyard mines in the Kanchanaburi replaced Outback mines in Queensland as main source of affordable commercial-quality sapphire. To regain lost leadership status, Australia must find new sapphire deposits with better-grade material or else find high-tech touch-up techniques. Otherwise, this country is destined to marginal importance for sapphire.

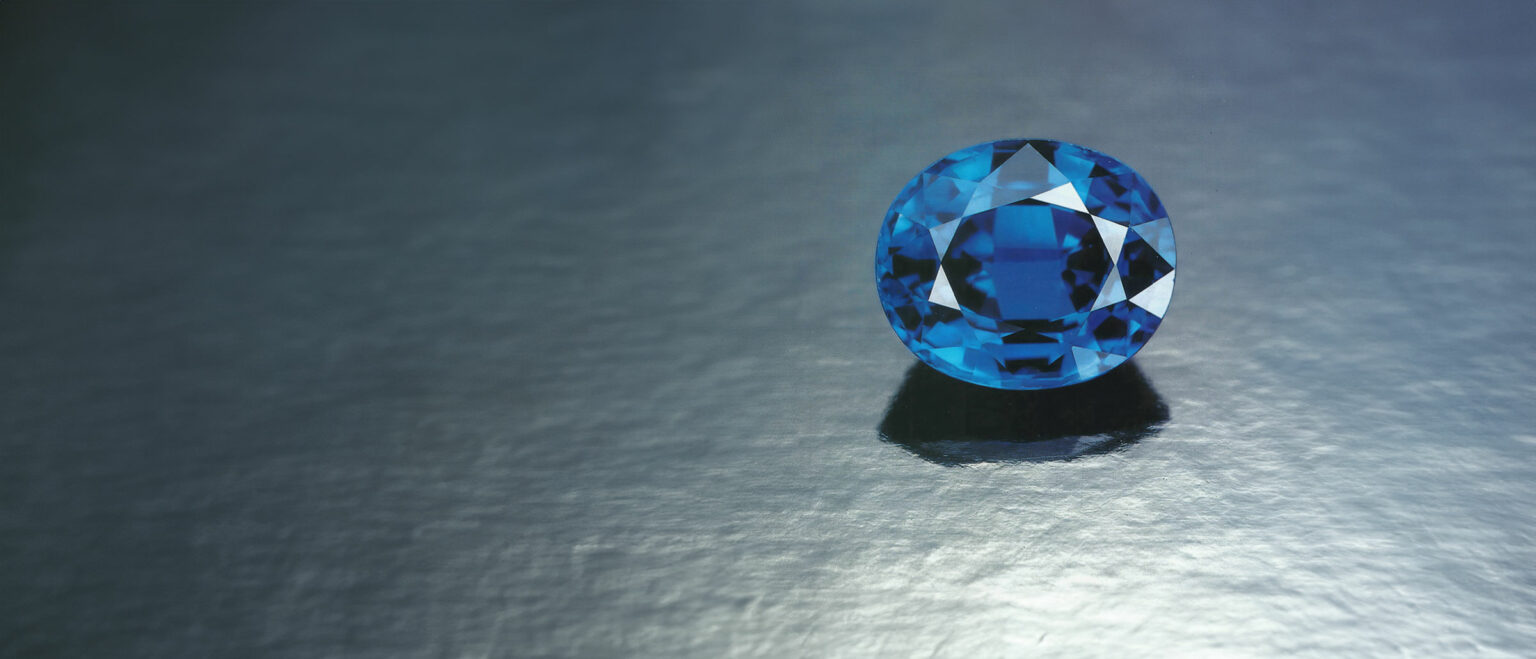

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1992 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles/2: The Second 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 1.61-carat Australian sapphire shown in the header image is courtesy of the Pan-American Diamond Corp., New York.