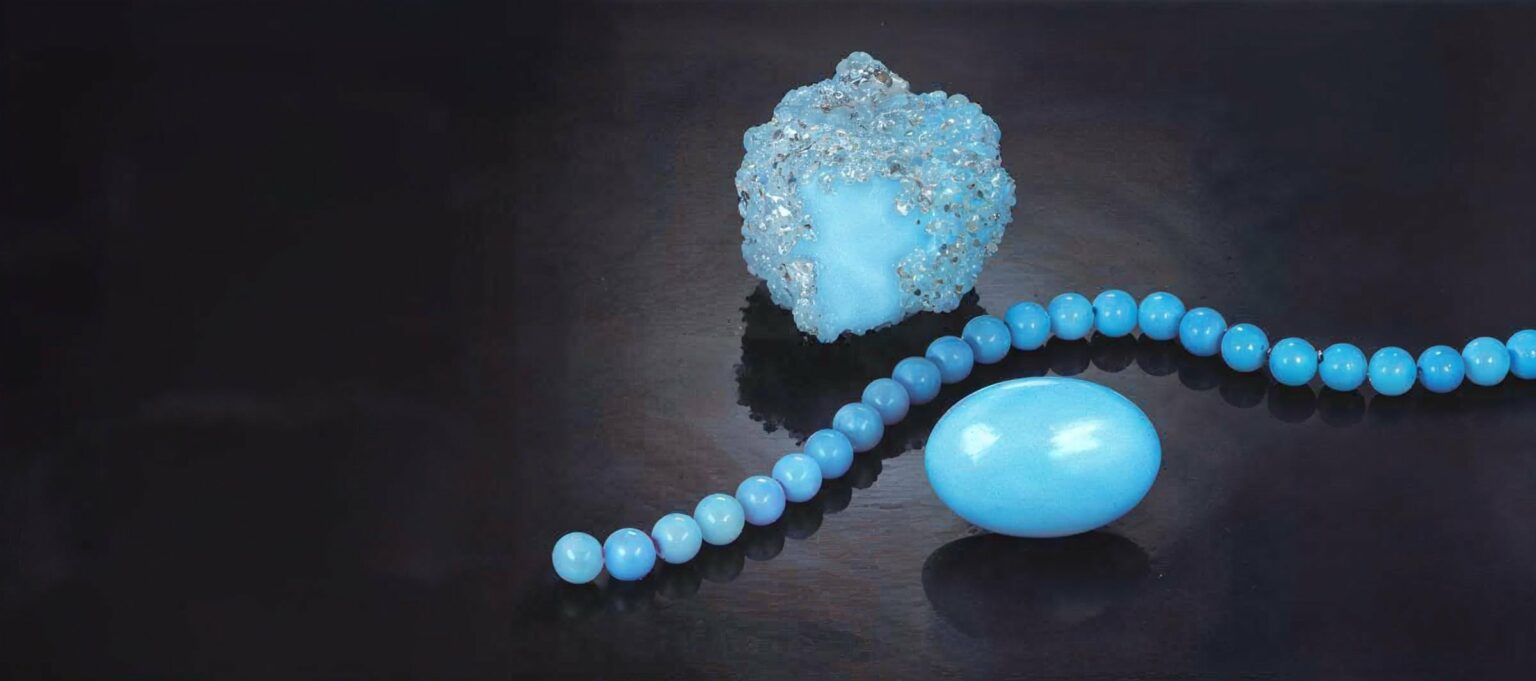

This sky-blue-color copper derivative, so important to the ancient Egyptians and Aztecs, has known better times.

Perhaps the best times of all for this gem were the late 1960s when social awareness briefly held more sway in U.S. fashion trends than the social registry. Back then, American Indian jewelry was powerfully in vogue and turquoise, the gem most associated with it, was hot.

But once so-called native Indian jewelry started coming from Hong Kong and Taiwan, with its turquoise often plastic treated or just plain plastic altogether, the gem’s popularity nosedived. It didn’t help matters when a major tribe of the Southwest was found to have mass produced some of the silver and turquoise jewelry in Asia that it had been selling as handmade in the USA.

Such scandals devastated the reputation of a gem that is as strongly linked to centuries of skillful jewelry artisany and other decorative arts as amber and ivory. Yet even with such scandals, there were still small but evidently gold-lined pockets of connoisseurship for this gem. Los Angeles turquoise specialist Robert Magobian, R.H. Co., recalls prices to Iranian collectors of as much as $2000 per piece for topechelon 15X20mm turquoiuse cabochons as late as 1976.

A decade later, it is doubtful that the finest turquoise could fetch anywhere near that price—unless a part of an important piece of antique jewelry. The sad truth about this gem is that rampant adulteration, plus a profusion of fakes, has cost this much of the public’s trust.

Persia Spelled A-R-I-Z-O-N-A

Like copper, the metal of which the gem is a by-product, turquoise is abundant at a time when demand has slackened considerably. The end a result: ravaged prices. Indeed, output from turquoise mines in Arizona alone, presently the gem’s biggest producer, is said to be around 1,500 pounds a week. Most of this material is sent to Hong Kong and, increasingly, Italy for processing. But American dealers like Hagobian often get to skim off the best grades.

Although the U.S. Southwest is well-known for turquoise mining, Arizona is not the place most jewelers and connoisseurs think of when they think of turquoise. Very likely Iran comes to mind for Iran-or should we say, Persia—is to turquoise what Burma is—to ruby: the premier source.

Just for the record, however, the earliest known deposits of turquoise were found in Egypt, at least as far back as 2000 B.C. Ironically, grades were so poor that Egypt’s jewelry artisans were forced to develop a substitute composed of a quartz paste that was shaped to look like pieces of turquoise, then glazed a beautiful sky-blue color before being hardened in a fire oven. Called faience, these turquoise simulants fooled antiquities experts until recently.

Given the largely mediocre quality of Egypt’s Sinai-mined turquoise, it is hardly surprising that so few jewelers know of its role in history. Ancient Persia is widely believed to be the first, as well as the best, source of turquoise. And for many purists, it is the only source. That’s why much of the fine turquoise sold today is sold as “Persian.” Only it’s not. Mining activity in Iran is negligible at best. “Most of the turquoise sold as Persian today really comes from America,” Hagobian says.

Now many readers might find this evidence of continued turquoise charlatanry. But, in reality, American turquoise boasts its own grand, but far less celebrated, heritage.

Memories of Mexico

American Indian jewelry is primarily identified with three tribes: the Navajo, Pueblo and Zuni. Actually, turquoise veneration and use here reaches back centuries to the time when New Mexico, a major U.S. turquoise locality, was a part of the great Aztec empire of Mexico (1300 to 1520 A.D.).

To the Aztecs, turquoise was a commodity more valuable than gold and a principal decorative medium. Even after the fall of the Aztec empire to the Spaniards, turquoise maintained its importance to the Indians, despite brutal attempts by their oppressors to confiscate it.

Few know it, but turquoise is synonymous with political liberation to the Pueblo tribe. For more than a century, its members were forced to work both underground and open-pit turquoise mines for Mexico’s Spanish conquerors. Then, in 1680, after a major mine cave-in killed scores of workers, the Indians refused to work. Instead, they staged a rebellion and drove the Spaniards from their lands.

Such victories over what today is called imperialism would have probably added even more to the pleasure of turquoise ownership back in the Vietnam era. But the intricate involvement of turquoise in Mexican and U.S. political history was pretty much ignored then—and now. No wonder some turquoise zealots consider it a mark of alienation from our past that more reverence is given to the Persian rather than the American variety. But defenders of Persian turquoise say the preference is based on aesthetics.

The Blue-Sky Ideal

Talk of ideal color in turquoise today is, admittedly, a little beside the point since manufacturers here and abroad are reluctant to pay any more than $3 per carat for the oval, pear and round cabochons they buy, usually $1 per carat is more like it. For this kind of money, they generally receive mild to medium sky-blue colors, rarely, if ever, the intense deep-blue azures extolled by the experts.

Given the extremely low prices of high-grade natural turquoise, it is somewhat amazing to find a thriving market in treated material. The market is as old as love of turquoise, starting with the imitations of ancient Egypt. But the ancient imitations made sense because the gem was then genuinely precious—not to mention scarce relative to demand.

By the late 19th century, however, when fine turquoise was quite inexpensive, the tricks played with turquoise were much harder to condone. American gemologist George F. Kunz caused a sensation when he exposed the infamous “Berlin-blue” dyeing technique around 1900. But detection didn’t deter even more ingenious deceits.

That’s the biggest threat to the turquoise market today: ever more clever forms of doctoring such as stabilization with polymer binders to increase durability. While polymerized turquoise is understandable given the fact that the gem is very soft and porous, some recent laboratory concoctions that contain as little as 5% of mineral are not. Such fakes are especially hard to countenance given all the natural turquoise and natural-turquoise substitutes such as azurite and chrysocolla on hand at rock-bottom prices.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The turquoise pieces shown in the header, including the 4.5 mm bead strand and the 20x15mm cabochon, are courtesy of R.H. Co., Los Angeles.