Despite Tiffany connections and a large connoisseur following, tsavorite is becoming something of a has-been. And the very thing that should be helping the faltering career of this green garnet, strong family ties to much-coveted demantoid garnet, is hurting it. Indeed, tsavorite seems cursed by déjà vu as it follows in the footsteps of demantoid.

Although demantoid took the jewelry salons of Paris and New York by storm after its discovery in Russia’s Ural Mountains in 1868, its vogue didn’t survive the Victorian era because mining lasted less than 30 years. Many dealers predict a repeat of history as mining of tsavorite, an equally captivating grassular garnet found in Kenya in 1968, threatens to die out even sooner.

“Tsavorite is the 20th century’s demantoid,” declares Bill Larson, Pala International Inc., Fallbrook, Calif. “Of between 40 and 50 mines worked since the late 1960s, only one of any importance is operating. The other few are small and their production of fine stones is practically nil.”

But Campbell Bridges, the mining geologist who is credited with having discovered tsavorite and persuaded Tiffany to promote it, dismisses such judgments as premature. “There’s enough tsavorite coming from Kenya to make it a genuinely commercial gemstone,” he says.

That’s debatable. By Bridges’ own count, only four tsavorite mining ventures have output of any consequence, hardly enough, at this point, to guarantee a flow of the garnet anything like that 15 years ago. And even then, tsavorite wasn’t all that abundant. As production has dwindled steadily throughout the 1980s, dealer pessimism has increased inversely.

Nevertheless, specialists in East African stones assure us the tide is turning. “As Karim Jan of Tsavo Madini, Costa Mesa, Calif., explains, “Politics, not geology, is what has held back tsavorite.”

A Visit to the Bush

Imagine yourself in a flat, arid grassland, studded with hills and extinct volcanoes, that stretches roughly 40 miles from the Tata hills of Kenya into next-door Tanzania. Every once in a while you may see a farm, but for the most part, this is snake-infested bush where prowling lions are not unusual. This area, approximately 800 square miles, is tsavorite country.

Tsavorite (name Tiffany marketers derived from Kenya’s famous Tsavo Park in 1974) is found only in East Africa. Because of the region’s geology, described by gem dealer Colin Curtis, Gemological Exploratorium Corp., Tuscan, Calif., as “warped and convoluted,” tsavorite is a maverick mineral. Deposits, perhaps “pockets,” would be a better word, are usually small and unpredictable. “Seams just pinch out without leaving any indication of where they pick up again,” Curtis explains. “It’s very frustrating, to say the least.”

As befits such torturous deposits, rough crystals themselves show evidence of taking one hell of a beating in the ground. Due to tremendous volcanic heat and pressure, it is rare that dealers find sections of rough more than ¼ inch in length that are clean enough to cut. The remaining areas of the crystal are usually shattered. Dealers work with what are described as rough ‘pieces and sieves. Natives call these irregular-shaped crystals “potatoes.”

Given such brutalized rough, it is hardly surprising that cut tsavorites over 3 carats are exceedingly rare. Ironically, demantoid garnets were also rare in sizes over 2 carats.

To get at this tsavorite, especially that embedded in the hills, takes expensive earth-removal equipment run by currently ultra-expensive diesel fuel. All this requires lots of venture capital, a commodity that doesn’t flow as readily into Africa nowadays as it did in the 1970s.

Should mining money start flowing again, dealers like Curtis are not like that tsavorite production would reach old peaks. “It’s not like there’s no more tsavorite in the ground,” he says. “If you’ve ever been in the mining region, you’d have seen tsavorite outcroppings all over the place.”

A Green of Its Own

Nevertheless, doubts about tsavorite’s future have begun to take their toll. Not exactly a mainstream gem, tsavorite has found wide acceptance among custom jewelers. But even some of these tsavorite loyalists have turned to alternatives like chrome tourmaline, another East African gem.

“It’s a real ‘Catch-22’ situation,” worries Larson. “The inadequacy of production leads to decreased demand. Decreased demand then discourages further production.”

Tsavorite must break out of its present downward supply-dich demand spiral if it is to keep the small but solid jewelry niche it has earned for itself. That is exactly what miners like Bridges are trying to convince the trade is being done.

Bridges is making the rounds of American gem dealers and jewelry manufacturers pitching clean, well-cut, good-color tsavorite in smaller sizes as an ideal alternative to emerald. “It’s cheaper, harder and more brilliant than emerald, plus it is untreated,” he stresses. “That makes it a far better gem to pair up with diamonds.”

Interested buyers invariably respond to Bridges with questions about supply. Bridges estimates that present Kenyan tsavorite ventures can provide 2,500 carats a month of decent material in sizes up to 33 points costing between $65 and $200 per carat on a steady basis for the foreseeable future. “I know the caratage is a drop in the bucket compared to emerald,” Bridges concedes, “but it’s a basis for the beginning of a manufacturer commitment.”

No matter what happens with jewelry manufacturers, however, tsavorite is likely to stay a favorite of collectors and investors. For one thing, it boasts almost non-stop price appreciation since the early 1970s. “I can’t recall any speculative periods for tsavorite prices,” says noted New York lapidary Reggie Miller, Reginald C. Miller Inc., “just steady, orderly growth.” One reason for the interest, a reason Bridges is trying to exploit with jewelry makers, is that tsavorite benefits favorably from comparison to emerald. “It’s the gem emerald should have been,” he says, “equal in color and superior in every other regard.”

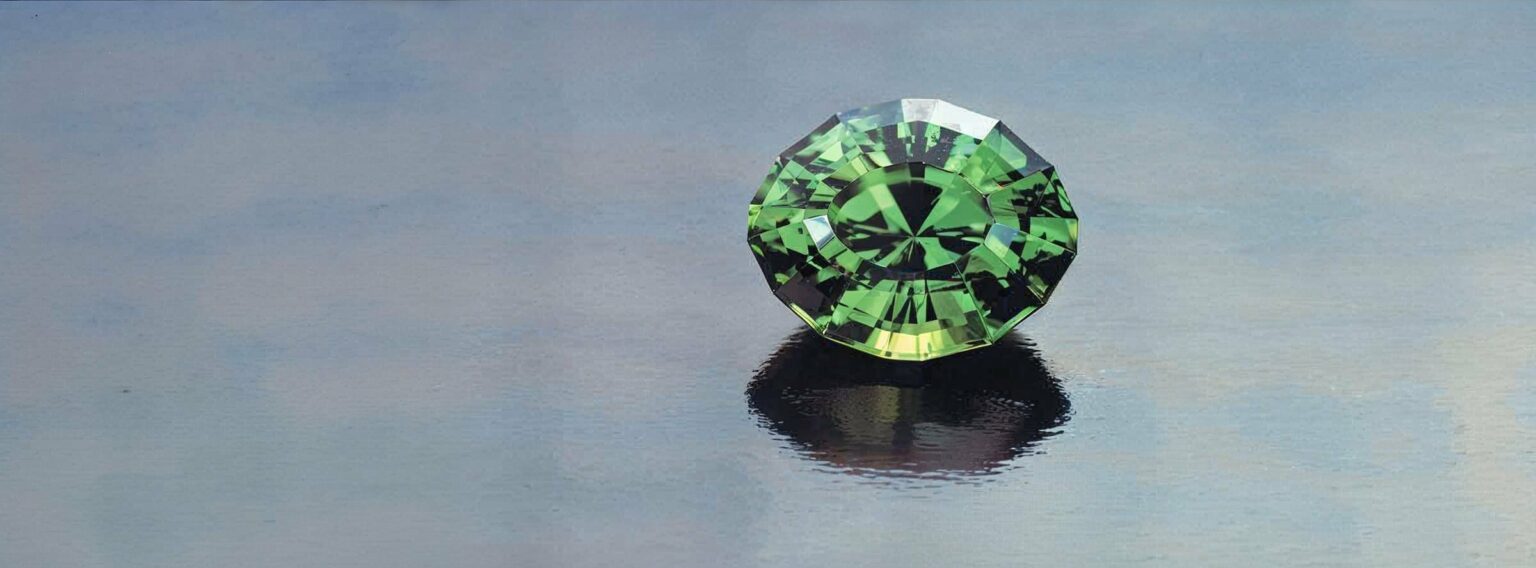

When buying tsavorite, dealers say to expect eye-clean stones. With regard to color, jewelers should look for a green that is reminiscent of that found in imperial jade. Failing to find that, stones with what Miller calls “a lime-Jell-O green” are acceptable. But avoid stones that are a light soda-bottle green or overly blackish and dark. According to our dealer survey, fine to superb tsavorite will cost $75-$100 per carat in 1- to 1½-carat sizes and as much as $2,000 per carat for comparable grades in sizes up to 2 carats. “Above 2 carats,” says Larson, “tsavorite is priced by the stone.”

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 2.34-carat tsavorite shown in the header image was courtesy of Tuckman International, Seattle.