One by one, the world’s most renowned deposits of blue sapphire are running dry or simply not running at all. Kashmir, the supreme source, has been a lost cause since the 1920s. More recently, in 1962, Burma sealed off her fabled Mogok tract, leaving the world dependent on intrepid smugglers for the greatly diminished supply of her coveted corundums. In 1974, Cambodia’s famed Pailin region was decreed, and has remained, off-limits to gem mining. And around 1980, Thailand’s Kanchanaburi sapphire fields ceased to be worth the time and trouble to work.

All this, says New York dealer Abe Nassi, has left Sri Lanka (still stubbornly called Ceylon by old timers) “the only steady producer left of large fine sapphire.” Now some may argue that Montana’s sapphire-rich Yogo Gulch could reemerge as a reliable source too. But so far, chronic financial woes that plague every recent attempt at mining there have left it more a source of big hopes than big stones. No such hopes are entertained for Australia, the world’s cornucopia of low-end blue sapphire, or newcomer East Africa.

So when it comes to newly mined, fine blue sapphire, Sri Lanka is now the standard bearer for this species. Her status as the world’s prime present-tense producer of fine blue sapphire comes at a time when Sri Lanka continues to grow as a sapphire mining center. Dealer Razen Salih, a major gem merchant in Saudi Arabia, reports that several finds have been made recently in southern Sri Lanka. “The goods are there,” he says. But he quickly notes, “Fine sapphires are the scarcest they’ve been in decades.”

The reasons, Salih believes, have more to do with man than nature. A fierce battle for control of the Sri Lankan sapphire market is driving prices for goods to dizzy heights. And the strong comeback of the fine goods market since the start of the dollar’s long decline in September 1985 has only accelerated this trend.

From Blah to Blue

Sri Lankan sapphire, like Brazilian aquamarine, is a stone that is customarily heated to improve color. The use of low-temperature, charcoal-fire heat has been used for centuries in Sri Lanka to sharpen hue. But this method has limited application. It didn’t do much good for the vast number of the country’s milky, ruddle-ridden stones.

Some time in the mid 1970s, gem dealers in Thailand began to experiment with high-heat kilns and later controlled-atmosphere furnaces to transform once seemingly heat-resistant sapphires from colorless to color-fast corundums. To experienced eyes, these heated stones were distinguishable by their pronounced color zoning, altered inclusions and, on occasion, their “scorched” color.

“The impact of the new heating technology was felt far more in the commercial than the fine goods sector,” says well-known New York lapidary Reggie Miller, Reginald C. Miller Inc. “There was suddenly an enormous influx of pleasing lower and middle cost Sri Lankan sapphire.”

The influx couldn’t have come at a better time. As 1970s inflation drove up sapphire prices and Far East Asian political turbulence disrupted fresh supplies, Sri Lanka’s heatable sapphires became a godsend. By 1980, word was out that Thai dealers had found a way to coax color out of what formerly had been considered incorrigible corundums. Now known as “Geuda” stones, these redeemable roughs began to command higher and higher prices. Thai dealers, the sole possessors of the new high-heat color technology, were willing to pay those prices. Sri Lankan dealers watch helplessly while Bangkok replaced Colombo as the world’s corundum capital—at least for commercial material.

“To become the true leader,” says New York fine gems expert Isaac Aharoni, Isaac Aharoni Inc., “Thailand must of the same complete range of sapphire from top to bottom.”

All Natural or Nothing

In the last few years, Thai dealers have been making a bid to dominate in fine sapphire as well as intermediate and lower grades. One way they are positioning themselves as fine sapphire specialists, equal to Sri Lanka’s best, is to discretely comb the American market for treatable and non-treatable sapphires. Often working through European and American proxies, the Thais have taken advantage of lag-gard prices in the U.S. fine goods market—due entirely to the dollar’s slide since September 1985. There they can pick up stones for 20%-25% less than they can be sold for in Bangkok and as much as 40% below their price in Colombo. The bargains exist because U.S. jewelry manufacturers and retailers balk at upward cost adjustments for sapphire as the dollar loses purchasing power against the yen, Swiss franc and Deutsche mark.

But while the U.S. fine sapphire market remains low-key, the international market has re-ignited. Significantly, many buyers of fine, large sapphires are demanding that stones be unheated—and documented as such. Cap Beesley of American Gemological Laboratories in New York, says, “More and more buyers are making purchase of fine sapphires and rubies conditional upon inspection by stones for treatment and clearance of them as natural.” By “clearance,” Beesley doesn’t just mean issuing a certificate that is free of any damning heat-treatment comments. Such certificates leave room for errors of omission. Therefore, Beesley continues, “Buyers want to see an explicit positive comment that the stone is straight.”

Miller, one of the few dealers who warranties in writing that Sri Lankan sapphire is all-natural, is not surprised. “It’s only right,” he declares, “that a person paying top dollar for a sapphire know that it didn’t start life a worthless pebble in need of doctoring to attain its beauty.”

Accordingly, jewelers should expect to pay anywhere from 30%-50% more for a fine Sri Lankan sapphire from 3 carats up that is certified uncooked by either the AGL or the Gemological Institute of America. So, for instance, the all-natural counterpart of a fine heat-treated 3-carat stone currently costing around $2,000 per carat will command between $2,600 and $3,000 per carat. In the case of sapphires of 10 carats or more, the premium for untreated stones starts at 50% and moves higher, depending on size and beauty. The premium could widen considerably and a full-fledged two-tier market emerge for unheated as opposed to heated sapphire as the public becomes more aware of treatment. This is more possible than ever before now that the American Gem Trade Association, a leading U.S. gem group, has prepared a disclosure system, endorsed by retail groups like Jewelers of America and the American Gem Society, to inform consumers about this sensitive subject.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

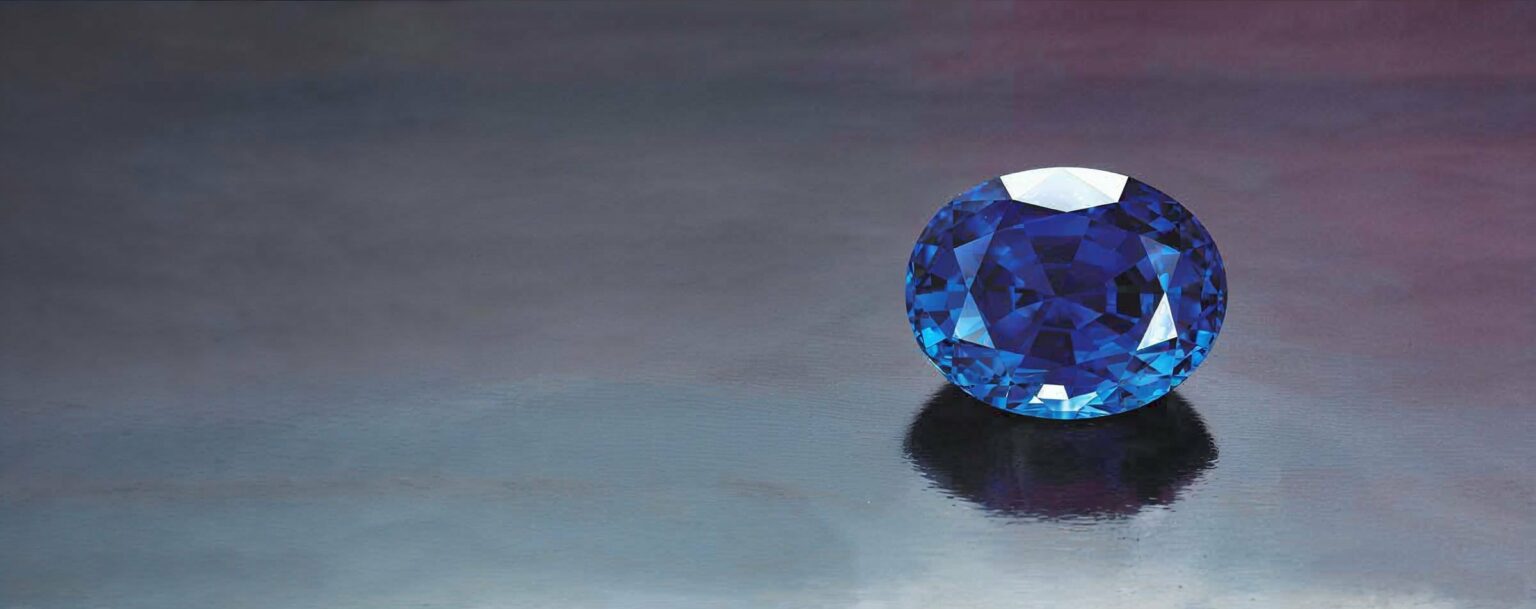

The 11.75-carat Sri Lankan sapphire shown in the header image is courtesy of Reginald C. Miller Inc., New York.