Once upon a very real time, nearly 20 years ago, some miners in East Africa went looking for a purplish-pink garnet called rhodolite which was very popular in Japan. One day, while digging for rhodolite, the miners found a strange orange and sometimes reddish-orange garnet mixed in with the pink garnet.

“What is this stuff?” one asked. “I don’t know. But whatever it is, no one will want it,” another answered.

And, sure enough, the Japanese kept rejecting this new garnet when offered it by dealers in Nairobi, Kenya. In time, the African dealers came to treat the gem with contempt.

Gradually, as miners kept finding more of this nuisance gem, they nicknamed it “malaya,” a Swahili word that means, first, “outcast,” and second, “prostitute”—but connoting, above all, trash. They called it malaya because that person told them to stop bringing this new gem to them.

Then, one day in the late 1970s, some Americans (and Germans, too) happened to notice the orange garnet and began questioning the African dealers about it. “Oh, you mean the malaya?” the dealers would say, a bit surprised. “What’s malaya?” the Americans would ask.

“It’s a misfit garnet that no one has any use for,” the dealers invariably replied. “But it’s beautiful,” the Americans would insist, and buy some still to collectors back home.

In no time at all, the new garnet went from outcast to “in” thing. And prices for top grades quickly flew to $50-$60 per carat from next to nothing. When the Americans discovered that the gem was a completely distinct breed of garnet, prices for top stones quickly winged past the $100-per-carat mark and roosted comfortably around $175 per carat.

Today, despite greatly slackened demand, fine malaya still commands nearly what it did when it took the American market by storm in 1979.

The moral of this true story is this: One man’s garnet is another’s gold. Especially when it comes from East Africa where garnet breaks all the rules.

Playing Pygmalion

Although malaya is no longer an outcast or misfit, the name still sums up the gemologist’s frustration with this garnet, much as it once did the dealer’s. Malaya is a mongrel garnet, part grossular, pyrope, almandine and spessartite. Some gemologists have already labelled it part of a garnet group called pyralspite to convey that it is basically a cross between pyrope, almandine and spessartite.

Visually, malaya most often resembles spessartite and hessonite, two brownish-orange to orange garnets that are as rare as this newer species. Nevertheless, the idea of paying as much as $150 per carat for any of these three garnets, no matter how rare, is something many orthodox precious stones dealers cannot stomach—although they routinely charge $3,000 per carat for more readily available fine 1-carat rubies. Indeed, a couple of these dealers tell us that the malaya market is a hoax and that no garnet, excepting demantoid and tsavorite, should cost more than $100 per carat in the trade. For these dealers, the word “garnet” still conjures five-and-dime birthstones and class ring pyropes.

But to gem collectors and connoisseurs, by far the main audience for malaya, the new garnet has earned full respectability. It may even be fair to say that malaya is the most coveted non-green garnet—outside of exceedingly rare rhododendron-color rhodolite and some of the more remarkable of the color-change garnets coming out of East Africa.

In recognition of malaya’s new respectability, some prim and proper Europeans are trying to play Dr. Doolittle and have the name changed to “umbalite,” after the Umba Valley region of adjoining Kenya and Tanzania where the new garnet is found. But American dealers won’t hear of it. “The name ‘umbalite’ is nowhere near as euphonious as ‘malaya,’” says Los Angeles dealer Pete Flusser of Overland Gems. One of the earliest marketers of malaya, Flusser thinks the industry should stick with the stone’s original name, just the way it has with “tanzanite,” the trade name for a zoisite that is also found only in East Africa. “Malaya is such a beautiful-sounding word,” Flusser says. “The trade will continue to call it malaya, even if the species nomenclature is changed to umbalite.”

Meanwhile, the Europeans continue to play Pygmalion with the malaya name. “Leave well enough alone,” urges Karim Jan, Tsavo Madini, Costa Mesa, Calif. “The name is a great selling point.”

Sunkist Color

Although malaya resembles other garnets, the best of the breed have a distinctive pure orange color. In fact, Flusser jokes that most true-color malayas should come stamped “Sunkist” because their color is exactly that of a California orange.

Occasionally, malaya possess a beautiful pink-orange which dealers aptly describe as “peach.” Due to the rarity of these peach-colored stones, prices for them are quoted to us as high as $175 per carat when stones are clean and weigh between 5-10 carats. The more common “Sunkist” variety peak at $150 per carat for top qualities in the same size range. Reddish stones go for a bit less. Throw in some brown and the prices will begin to tailspin considerably below $100 per carat.

At present, dealer stocks of true malaya garnet are more than ample, particularly in Idar-Oberstein, Germany’s renowned colored stone cutting center which is famous for African gems. This is good news because mining of malaya is at an all-time low in East Africa, still this gem’s only known source.

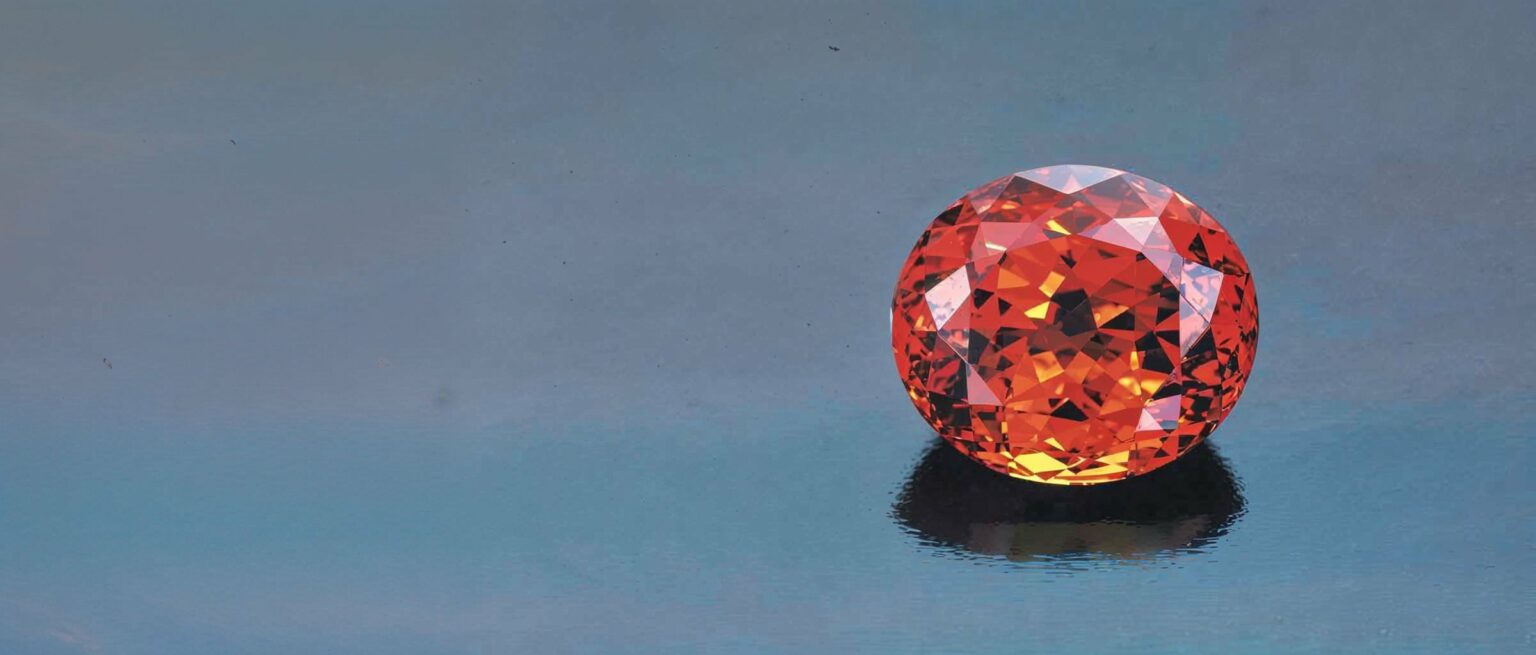

One last note: Jewelers should be aware that thousands of carats of junky brown garnet, worth no more than $10 per carat (and probably far less), were sold to countless gem investors as “malaya” in the early 1980s. We have seen so-called portfolios that featured these reject stones. There is a chance that some jewelers have been shown these garnets by investors anxious to unload them. If that is your first experience with malaya, please look at the marvelous 14-carat stone shown on the opposite page. Rest assured, those ugly brown garnets that investors bought are not malayas—not even low-grade ones.

“It is high time that many people including jewelers were exposed to imposter malaya,” Flusser says. “If so, they should give this beautiful gem a second chance. That’s what the Africans who named it malaya in the first place did—and their change of attitude made them money.”

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 14.19-carat malaya garnet shown in the header image is courtesy of Mayer & Watt, Beverly Hills, Calif.