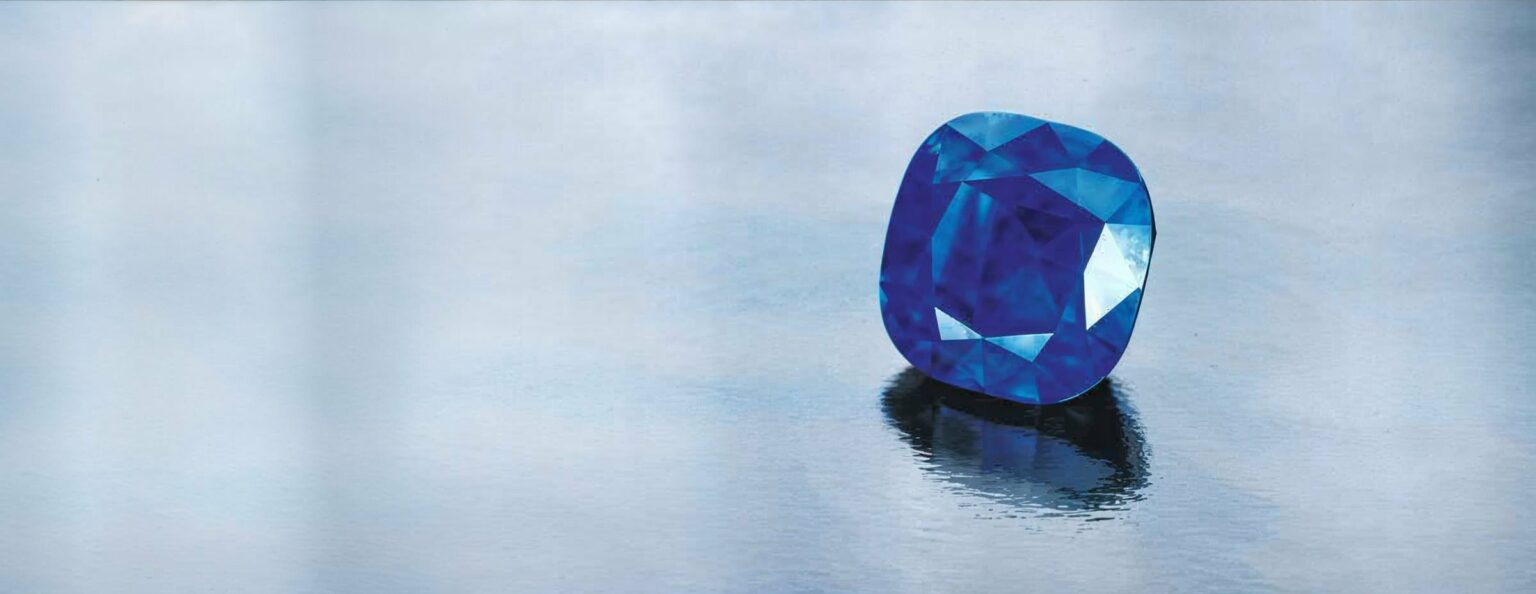

The stone’s blue is rich, royal and velvety, the quintessence of sapphire color. And because the gem is 24 carats, the telltale color banding that supposedly confirms Kashmir origin is immediately noticeable. Beyond such details, the eye-watering beauty of this sapphire is hard to convey.

Astonishingly, this magnificent gem, which has less than tracking it back at least 75 years, probably sold for perhaps $1 per carat when it was in rough state. Today, the fine-finished masterpiece is available at an adamant $200,000 per carat, close to $500,000. What’s more, its owner, a major New York dealer says it would have brought him $25,000 per carat in 1980, during the last gem bull market.

But if $200,000 per carat strikes you as too steep for a sapphire, even one so pedigreed, the same dealer has another Kashmir stone, this one only six carats, for sale at $15,000 per carat. Smaller size and a slightly lighter tone prevent him from asking more. Yet this stone, which its owner casually dismisses as “fine but not gem,” is better than most sapphires jewelers and dealers may ever see. Once again, the color is a serenely soft, almost princely blue with the same give-away color banding. When put next to a fabulous 8-carat Sivekananaphill sapphire, the latter seems sharper, cooler, less sensuous (although still gorgeous).

So much for the ineffable beauty of Kashmir sapphire. Rarely, except in a few tanzanites, has this writer seen a blue that was as awe-inspiring. And yet, these Kashmir sapphires may fall far short of the standard this species set after it first flooded the gem market late in the last century.

Blasé Abundance

Believe it or not, when sapphires were discovered around 1882 in Kashmir, a small Indian state in the Himalayas, they were so plentiful and large that locals would pick them off the ground to use as flint stones. When they realized these rocks were facetable, they took them to Indian dealers in places like Delhi who bought them as amethysts for pennies a carat. Later, when the gems were properly identified as corundum, prices jumped. Gemologist Max Bauer reports in the 1904 edition of The Systematic Description of Precious Stones that the usual price for Kashmir sapphire rough in London, then a major colored stone cutting center, was 20 pounds (or $120) per ounce (86 cents per carat).

Who could have foreseen that the Kashmir deposits would be nearly depleted by 1925? Yet, even when veteran New York lapidary Reggie Miller, Reginald C. Miller Inc., was learning this craft in London during the late 1930s, trade prices for polished Kashmir sapphire never exceeded $500 per carat. “And, by then,” Miller adds, “production from Kashmir was pretty much a thing of the past.”

Nevertheless, sporadic parcels still made their way to the West. Even today, smugglers continue to bring out occasional stones, despite heavy police guarding of the known mine sites. No official sales of Kashmir rough have taken place in nearly 20 years—although it was announced recently that mining would recommence. Meanwhile, the reputation of Kashmir sapphire endures so strongly that fine stones from this region are entitled to breathtaking premiums—based, in large part, on origin. The trouble is that proving origin is nowadays exceedingly tricky.

Provenance Problems

No matter what dealers say, selling a sapphire as Kashmir is usually more a matter of faith than fact. Indeed, many gems sold as Kashmir later turn out to be heated Sri Lankan stand-ins whose oven-induced color zoning was mistaken for the banding associated with the Himalayan variety.

For this reason, buying stones reputed to be Kashmir often involves what world-renowned New York gem dealer Ralph Esmerian, R. Esmerian Inc., describes as “agonizing judgment Calls.” Sometimes these calls have little or nothing to do with the stones and everything to do with the seller. “My decision is based as much on who shows me the stone and how it is the stone itself,” he continues. “If the person showing as just back from the Far East with a paper full of sapphires, he’s already got two strikes against him.”

Even when Esmerian is shown blue-ribbon laboratory reports that vouch for the stone’s Kashmir origin, he is not impressed. “The finest labs have been dead wrong,” he says. Far more important to him, as far as papers go, is document tat ion of previous ownership that can help him trace back the stone enough years to make him feel secure about its origin. The trade calls such documentation provenance and is becoming increasingly dependent on it.

Still, proving origin or, at least, becoming secure enough about it to begin negotiating for a stone on the basis of it is only the first step in acquiring a Kashmir sapphire. “There always comes a time for a one-on-one confrontation with the gem,” he says. “This is the moment when you give the stone a ruthless observation. That means forgetting everything you have heard about it and deciding for yourself what the stone is and if you like it. Just being a Kashmir sapphire is no guarantee of beauty or value.”

Such a confrontation takes confidence and chutzpah and is not recommended for anyone who only buys fine sapphires once in a while. Indeed, such a buyer may be better off ignoring origin, unless the person from whom he buys a Kashmir stone has impeccable credentials with such material and will attest to origin in writing. Miller does just that and, by so doing, accepts full liability should the stone turn out otherwise. That’s not likely, however, since Miller himself is often a court of last resort for other dealers when they want to be absolutely certain about origin.

Given the extreme difficulty of verifying Kashmir origin these days, many in the trade think origin selling is a dangerous anachronism that should be done away with. Instead, they favor judging a gem’s beauty and merit in terms of universal color grading systems. Advocates of this approach say that laboratory grades will reflect the inherent superiority of Kashmir color, thus protecting these stones’ values and, eliminating the need to sell locally.

Noted Brooklyn, N.Y. appraiser Ely Rosen says sacrificing origin and background and reducing a gem to a lab grade takes the all-important elements of “heritage and history” out of gem ownership. That’s a no-no for Kashmir sapphire, a gem that has a stature with connoisseurs that can be likened to that of a Rubens painting in the art world. “Just because authentication work is hard is no reason to take the easy way out and abandon it,” Rosen warns. “You let grading take precedence over everything else and pretty soon the colored stone world is going to be as sterile as the diamond world.”

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 3.03-carat Kashmir sapphire shown in the header image is courtesy of Mayer & Watt, Beverly Hills, Calif.