When tanzanite, a baked-to-blue zoisite from East Africa, took the jewelry world by storm in 1969, it was considered the poor man’s sapphire. But with prices of better material now several hundred dollars per carat, it may finally be time for iolite to try on the up-for-grabs mantle of sapphire substitute.

Certainly, its price is right, if not always its blue. Stones up to 3 carats rarely command more than $50 per carat, usually far less. And while larger sizes between 5 and 10 carats may sport price tags of up to $150 per carat, retailers and jewelry manufacturers usually let larger iolites go begging when their prices climb above $100 per carat.

Nonetheless, even $100 per carat is rather ritzy for this still largely unknown gem found today in India, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and, most recently, Brazil. A decade ago, the finest iolite was lucky to fetch half that amount. Back then, however, sapphire and its nearest look-alike, tanzanite, were far less expensive. So there was no pressing need for a sapphire substitute. But times have changed.

Pleochroic to a Fault

Iolite (the name comes from “ios,” the Greek word for violet) is commonly known as “water sapphire,” an apt description because its color very often lacks depth and density. One reason for this is the fact that iolite, like its fellow blue-bloods, sapphire and tanzanite, is pleochroic. That means that it transmits light differently in different directions of the crystal. Only in the case of iolite the pleochroism is so painfully evident that it is almost an affliction.

But that’s only when this gem is considered in a jewelry context. The Vikings (you know, the people who gave us Leif Ericson) made iolite’s pleochroism a virtue by using thin slices of this stone as a light polarizer. Believe it or not, iolite will do exactly what a camera’s polaroid filter will do: cancel out haze, mist and clouds to make things appear clearer. By observing the sky through iolite, Viking navigators were able to locate the exact position of the sun on overcast days.

Where, you might ask, did these famous seafarers get their iolite? Well, it’s been found in Greenland and Norway.

Meanwhile, iolite can confound and aesthete with its strong pleochroic stops and starts of color. For instance, an iolite cube shown us for this article was a sweet violet blue on one side, then gray white on the next. Its color literally disappeared, then reappeared, as the cube was rotated from side to side. No wonder some gemologists, ones unfriendly to iolite perhaps, call this stone dichroite. Actually, the name is wrong since this species is trichroic. But while the name “trichroite” may be more accurate, it is no less derogatory. Dealers partial to iolite, and there are a growing number of them, blame the cutters for making iolite’s pleochroism so problematic.

“You cut this stone the slightest bit off axis and you will flat-out destroy the color,” says Abe Suleiman, Tuckman International, Seattle. “But cut it right and this stone will stand up to comparison with fine sapphire. In fact, I’ll bet you that many jewelers at first mistake it for sapphire.”

Of course, for iolites to stand up to such high-praise comparisons and on occasion, the flattery of mistaken identity, they have to have good color in the first place. Many iolites are cursed with an ink-spot blue that makes them lovelies dark. Unlike sapphire or tanzanite, iolite cannot be heated to lighten color or bring out hidden beauty. What you find in nature is all you have to work with. And what you find in nature is very often disappointing, both from a standpoint of color and clarity. Thankfully, stones with good color but poor clarity lend themselves to cabochon cutting, a fate for a growing number of these stones. However, there seems to be enough stones with decent color and clarity to make a modest market in faceted iolite.

The Time Is Now

In actuality, a modest market for iolite seems to be emerging already. For years, jewelers have been buying iolite, sometimes unknowingly, as a sapphire understudy in popular rainbow gem jewelry. Iolite is plentiful in the small calibrated size needed for multi-color stone suites.

Unfortunately, iolite’s wide use in rainbow jewelry has not earned it a wide following. Few jewelers seemed to have noticed it. And few dealers seem to have made much ado about it. However, a small group of importers, some of them African stone specialists, have long predicted that iolite would eventually come into its own—provided there were ample supplies of larger, better stones. Are there?

Although we receive conflicting reports about current availability and production of this gem in decent grades (trash is plentiful), there is considerable accumulation of iolite, enough to support use of it on a fairly broad basis.

But that probably means traveling to Germany. Unquestionably, German dealers in Idar-Oberstein are the kingpins of the iolite market. Over the past few decades, they have patiently amassed enviable backlogs of this gem. Even today, the Germans are the most active buyers of iolite rough in the world. Given their role—and expertise—in past market-making for other new-arrival stones, U.S. dealers suspect that it is only a matter of time before the Germans turn their attention to iolite and push it here in earnest.

They already have. Based on their growing success with iolite in Europe, the Germans have been showing iolite in impressive bulk at recent editions of the Tucson Gem Show, the most important trade show for colored stones in the world, held every February. But because the Germans ask the highest we’ve seen, often in excess of $100 per carat for better stones in sizes over 3 carats, they have yet to make much headway. Our price surveys indicate that it is rare for an iolite to fetch more than $80 per carat. And even that is considered steep, especially when you consider that the Indians have been selling iolite to U.S. dealers for $20 to $30 per carat.

Nevertheless, we expect the Germans to stick to their guns on prices, a reflection of their domination of the market and their confidence in iolite as an up and comer.

For good reason. Karim Jan of Tsavo Madini, Costa Mesa, Calif., a regular buyer of iolite rough in Africa, still the preferred source for this gem, informs us that buying has picked up in Hong Kong, especially among jewelry manufacturers there. Even manufacturers here, one of them Krementz & Co., Newark, N.J., tell us they are dabbling with iolite. With fine stones costing jewels $40 to $60 per carat that resemble sapphires costing them between $400 and $600 per carat, it’s easy to see why iolite is becoming to sapphire what NutraSweet has become to sugar.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

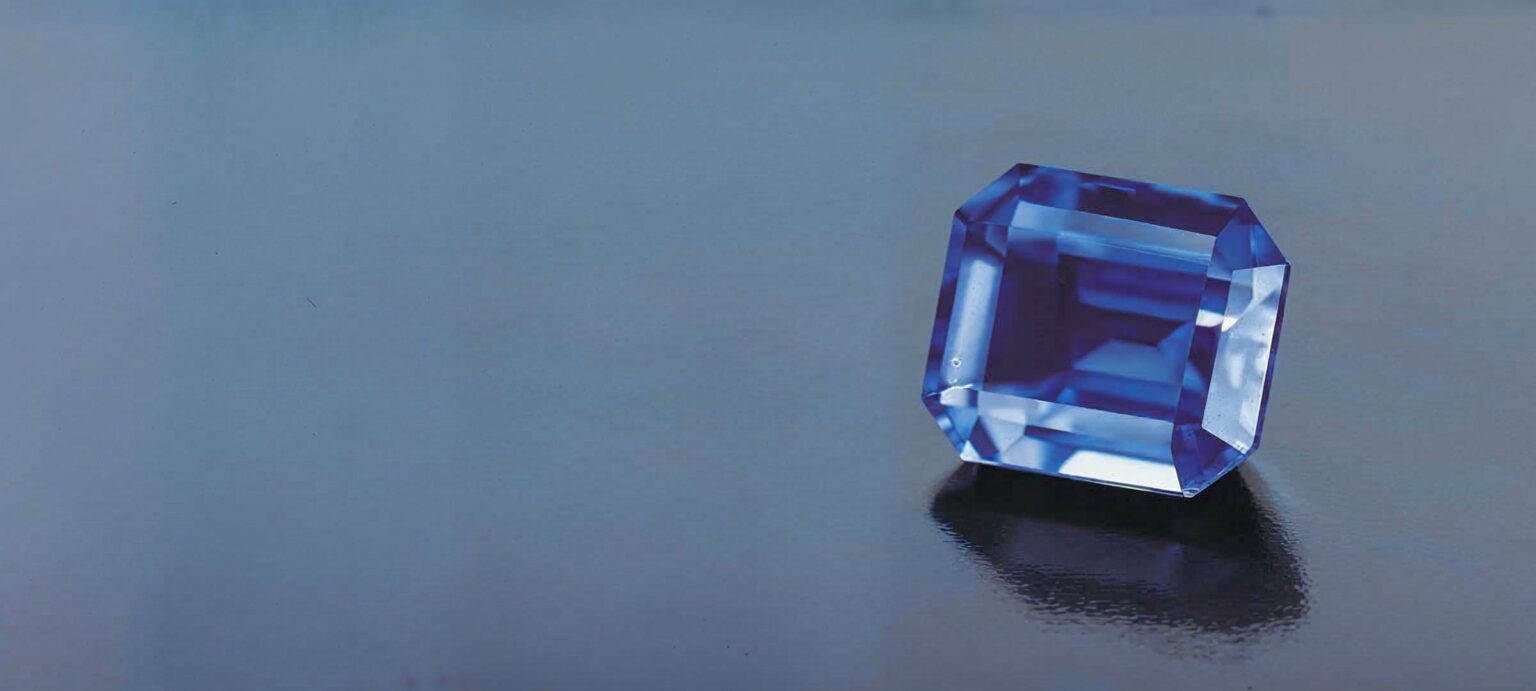

The 1.11-carat iolite shown in the header image is courtesy of Tsavo Madini Inc., Costa Mesa, Calif.