By now, East Africa has gained big league status as a producer of newcomer gems such as tsavorite and tanzanite. But it is still considered bush league when it comes to traditional stones such as sapphire and emerald.

For sure, the region is rich in these standbys. However, the quality of stones found so far is generally judged inferior to that from other active localities such as Burma and Sri Lanka for sapphire, or Colombia and Zambia for emerald.

That leaves ruby, which East Africa mines in abundance, to earn it the respect it craves as a source of stalwart gems. Ruby finds in Kenya have already begun to raise hopes. But no one is ready yet to raise glasses. “It all depends on whether the new deposits prove the rule rather than the exception,” says Abe Suleiman, Tuckman International, Seattle.

Judging from the number of Thai, German, Israeli and American dealers buying East African ruby rough in Kenya these days, it looks like better grades have become the rule.

“If production stays this good, East African ruby could be on the verge of full acceptance,” says East African gem expert Colin Curtis, Gemological Exploration Corp., Tustin, Calif. “The new production gives Burma and Thailand (the prime sources of ruby) a real run for the money.”

What has the newer East African ruby got that older stones from this region lack? And how good does that really make this ruby when compared to its Southeast Asian counterparts?

Burma Color, African Price

East Africa has been producing ruby in bulk for almost 20 years. Because most of its ruby is heavily included, less than 1% of the rough has been suitable for faceting. In fact, East Africa is known chiefly for cabochon ruby. Even now, with better grades more common, the number of facetable stones is minuscule.

However, what African ruby lacks in clarity, it more than compensates for in color. Indeed, up until 1980, as much as 15% of the output from the famed Longido mine in northern Tanzania was said to be virtually indistinguishable color-wise from medium-to-fine Burmese rubies.

Most other mines, ones such as Tanzania’s Morogoro mine, produced more purplish colors. This purplish (sometimes brownish) red, coupled with the stone’s coarse silk and super-numerous inclusions (most notably, liquid-filled cavities), gave the stones a flat, lusterless appearance when cut into cabochons.

Their dull, opaque appearance relegated East African ruby to use in low-end jewelry. As a result, it became associated primarily with Indian dealers in Jaipur who cut the lion’s share of this ruby.

Then sometime around the spring of 1984, miners started to unearth far more promising rough. News spread fast, so fast that Israeli and American dealers, among others, quickly flocked to Kenya’s two main gem buying centers, Nairobi and Mombasa, to bid on new parcels.

Thai Beautification

East Africa’s new ruby proved especially exciting to dealers in Thailand. Operating mostly through European and American agents, syndicates of Thai dealers began buying large quantities of the new material. Recently, in fact, Thailand have launched their own ruby mining ventures. Concurrently, there has been much-improved translucency and luster in Kenyan stones. Some in the market are convinced that these stones have been heat treated in Thailand. Others say they are simply the products of new finds.

Given Thailand’s reputation for gem beautification, it is easy to see why dealers would suspect that Kenya’s more comely rubies would owe their good looks to ovens. Nevertheless, East African gem specialists insist that, most, if not all, of these stones are natural. One of them, Karim Jan, Tatvand Madini Inc., Costa Mesa, Calif., says many Thai efforts at heating African ruby have failed. One reason: too many inclusions that could explode during the heat-treatment process and damage the stone.

Even so, say dealers who swear the Thai’s are heating East African ruby, the rewards outweigh the risks. According to Miami gem importer Richard Postrel, Gem Source Ltd., the color of Kenyan ruby is better than that shown by most Thai stones.

Second, while “expandable inclusions” do present problems, the new ruby takes nicely to heat treatment. “Using expensive, high-temperature ovens run in tightly controlled atmospheric conditions,” Postrel explains, “treaters in Thailand, including ourselves, can dissolve most of the coarse silk in the African ruby and produce very translucent stones.”

These stones, Postrel continues, are so close to Burmese ruby in color and appearance that “it pays to heat. African ruby is already being sold as Burma material on the Thai-Burma border. And some dealers have not even realized it.”

A Niche of Its Own

Despite the fact that East African ruby is often mistaken for Burmese ruby, it is highly doubtful that it will overtake either Burmese or Thai ruby any time soon in its standing among connoisseurs. Nevertheless, dealers believe it will play an important role in the mass jewelry market, especially in light of the resurgence of cabochon-gem jewelry.

For years, the Italians and, to a lesser extent, the French have been ardent admirers of East African ruby. Now with cabochon jewelry having made such a dramatic comeback in the United States, dealers here are betting that Americans will become devotees of African ruby too. “It’s a superb bluff stone,” Postrel says.

At present, better-to-fine East African cabochon rubies in 5-10 carat sizes are quoted to us at $500-1,000 per carat —with exceptional stones commanding as much as $1,500 per carat.

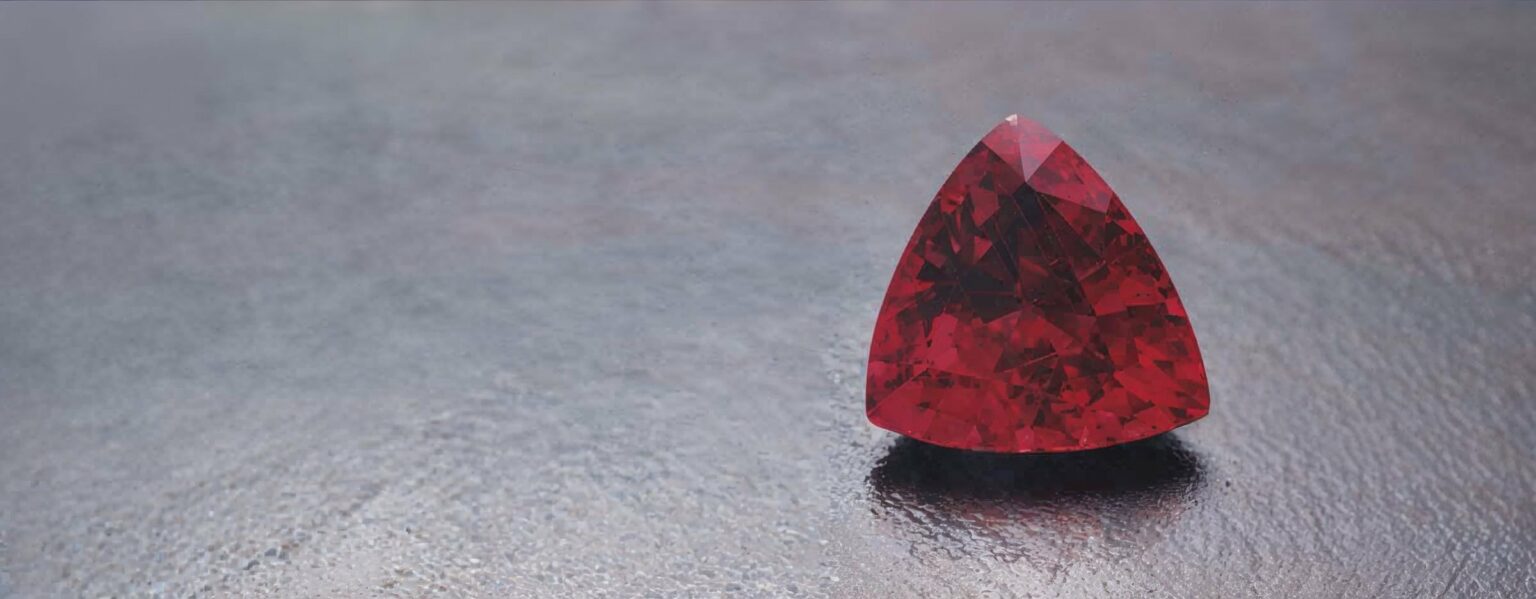

As far as color, expect stones with either a fine cherry red tinged with pink or a watermelon-like pinkish red. Stones should not be visibly purple or brown. As important, the stones should hold their color in both incandescent and natural daylight. That’s because they are highly fluorescent.

Regarding translucency and clarity, stones should verge on semi-translucency and be partially inclusion-free for up to 3-4mm below the surface when observed under penlight. Last, stones should not be cut with overly high domes or heavy bottoms. These are purely weight-retention measures that add nothing to the beauty of the stone—only its price.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 17.4-carat East African ruby shown in the header image is courtesy of Tsavo Madini Inc., Costa Mesa, Calif.