Quantity kills quality.

As an example, we cite the Shanghai lake district of China, the world’s prime producer of freshwater cultured pearls.

To boost harvests of these very popular pearls, most of which resemble Rice Krispies, the Chinese government has turned pearl farming there (and elsewhere throughout the country) into something of a numbers game with growers paid purely by pearl weight not worth. U.S. dealers who buy direct from the Chinese say this weight-over-worth policy has worked to swell output, currently estimated at between 75 and 80 tons annually—but at the expense of top grades. Only a decade ago, better goods accounted for a far more substantial share of overall production. Now they make up, some dealers insist, less than 10% of the country’s annual pearl crop. And the percentage is shrinking fast.

“I’m seriously worried about the future of quality pearls from China,” says Jesse August, August Corp., New York, a regular traveler to China. August isn’t alone.

The Big Shell Out

In the name of numbers, Chinese pearl farmers switched from the slow-grown sakaku to the fast-grow kurasu mussel during the late 1970s. Use of the kurasu mussel—which August estimates now accounts for 80% of Chinese freshwater pearl production—has cut cultivation time from 36 to as little as 12 months.

But abbreviated growing cycles take a heavy toll in terms of pearl beauty. Nearly all kurasu pearls lack the smooth, lustrous surfaces of their sakaku counterparts. Instead, they are wrinkled and dull, often severely so. Shorter shelf life also contributes to a marked decline in production of symmetrical shapes. “The Chinese are harvesting, for the most part, between 12 and 18 months,” says L.S. based pearl farmer John Latendresse, American Pearl Co., Camden, Tenn. “Your chances of getting symmetrical shapes are much better if you leave the pearl at least two years to grow.”

This isn’t to say that shorter growing cycles are the sole reason for Chinese pearl quality problems. Overcrowding of some lakes and ponds starves mussels of necessary nutrients to make fine pearls. And the comparative lack of Chinese pearl culturing know-how compounds the situation. “For 17 cents an hour, you’re not going to find technicians who know the niceties of pearl cultivation,” Latendresse declares.

Learning those niceties is the key to the future of the Chinese pearl industry. Despite experiments cross-implanting the tissue of the kurasu into the sankaku mussel for more shapely, less afflicted pearl growth, many Chinese pearl technicians lack the profound sensitivity and skill to make these experiments a pearl improvement succeed. “How can you produce in beautiful pearl if you don’t know the correct way to lay in the mantle tissue that serves as its nucleus?” Latendresse asks.

Proper insertion of mantle tissue is essential for decent freshwater pearls. Unlike Japanese akoya and South Sea saltwater cultured pearls, Chinese freshwater pearls contain no shell-bead nucleus to force spherical or, at least, symmetrical growth. Only sections of tissue from sister mussels are used, sometimes as many as 50 to a mussel, but usually closer to 25. As nacre forms around tissue, it does so in freer style, taking a range of shapes from roundish to rice, depending on the way the tissue is first implanted and then shielded from disturbance.

The Shanghai/Biwa Connection

China’s lack of sophistication with regard to pearl technology, coupled with its sheer-volume philosophy, put the country in a bind it is having difficulty escaping. At least 80% of the country’s yearly pearl harvests are rice pearls, 1.6-inch strands of which are readily available for as little as $1-$2 in Hong Kong and Taiwan. This abundance of low-grade material only reinforces China’s image as a second-class pearl power. Indeed, her best off-round and symmetrical pearls in 7mm sizes are lucky to command $6 per piece.

Yet many of these same pearls command three to five times this price in Japan where they are sometimes sold as pearls from that island’s famed Lake Biwa, an area so ravaged by pollution that the pearl-mussel mortality rate is reported running at 60%-70%. Nevertheless, few jewelers would guess that the lake is a mollusk death trap because of the large numbers of pearls that continue to be sold as Biwa in origin.

Statements that pearls from China’s Lake Shanghai come from Japan’s Lake Biwa are “clearly deceptive and violate the law,” says Joel Windman, general counsel of the Jewelers Vigilance Committee. Yet, maintains Latendresse, some dealers here and abroad rationalize such misrepresentations by arguing that Japanese high-tech enhancements of Chinese pearls make them, in effect, a Japanese product.

That’s stretching things. Nevertheless, many dealers who reject calling Chinese freshwater pearls Biwa have no qualms about labeling them as “Biwa-type” or “Biwa-like.” New York-based pearl publicist Alan Mawrence thinks this is equally wrong. “It’s deceptive to make an origin term like ‘Biwa’ into a generic term,” he says. “I have never seen a Chinese freshwater pearl equal in quality to the Japanese variety. Use of ‘Biwa-type’ makes it seem the only difference between the two is geographical.” Users of such terms say there is a very strong resemblance between the best Chinese freshwater and Biwa pearls—so strong, in fact, that it takes an expert to tell them apart.

According to one of those experts, Jesse August, Japanese look-alike pearls from China, a decided minority of that country’s production, are principally ones known in the trade as flats. “They’re similar to Biwa,” he explains, “but with one important difference: The Chinese pearls are only flat on one side.”

Thankfully, the confusion of Chinese with Japanese pearls affects a relatively small percentage of Chinese freshwater pearls. However, with Japanese freshwater production in big trouble, the Chinese have perhaps their greatest opportunity of the past 20 years to upgrade their overall image as a pearl producer. But they’ll need help from the Japanese.

It’s highly doubtful, however, that the Japanese will be open to any type of pearl pact with the Chinese. They remember all too well how they were ejected from Burma after helping to make that country’s pearl farms among the finest in the world.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

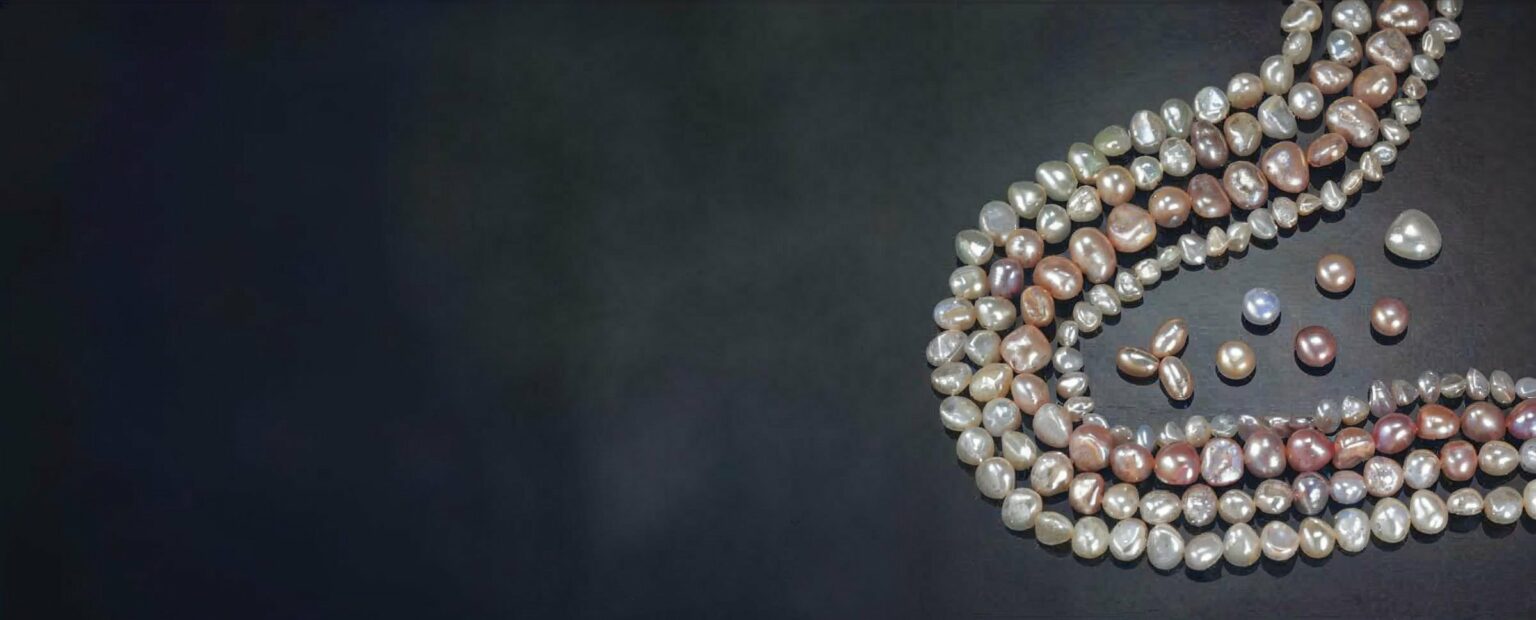

The Chinese freshwater pearls shown in the header image are courtesy of K.C. Bell of K.C.B. & Associates, Santa Monica, Calif.