In 1962, the last year Westerners were permitted to buy gems in recently turned socialist Burma, New York dealer Reggie Miller, Reginald C. Miller Inc., bought a large selection of very fine 20 to 40-carat peridots there for $1.50 a carat.

Some 25 years later, the best Burma peridot he can find is decent but not great and costs him $100 a carat. Based on such prices, Miller figures he would have to pay $150, perhaps as much as $200, per carat for top-grade material in sizes between 20 and 40 carats. “But I can’t find it,” he says. “Not in Asia or America.”

The paucity of fine large peridot comes, as is so often the case in the jewelry world, just when this gem is capturing lots of attention. Demand is not yet fierce, mind you, but it exceeds supply. Peridot’s status as the August birthstone, its pleasing green color and its bargain price relative to its extreme scarcity in top grades make it possible for dealers who carry this gem to sell all the fine-specimen large stones they can find.

“I wish I could lay my hands on enough large, clean and well-cut peridots to fill the calls I keep getting for it,” says Don Golden, Samuel Goldwinski Inc., New York. “The market wants peridot, but not the kind dealers can provide.”

What they can provide are smaller stones, generally under 3 carats, most from Arizona and, occasionally, Mexico where peridot is plentiful. But it’s the wrong kind of plenty. Because America produces almost no large stones, peridot is rarely seen in solitaire or center-stone jewelry. Rather, it’s used most frequently to lend accent or a multi-color effect.

Source spots

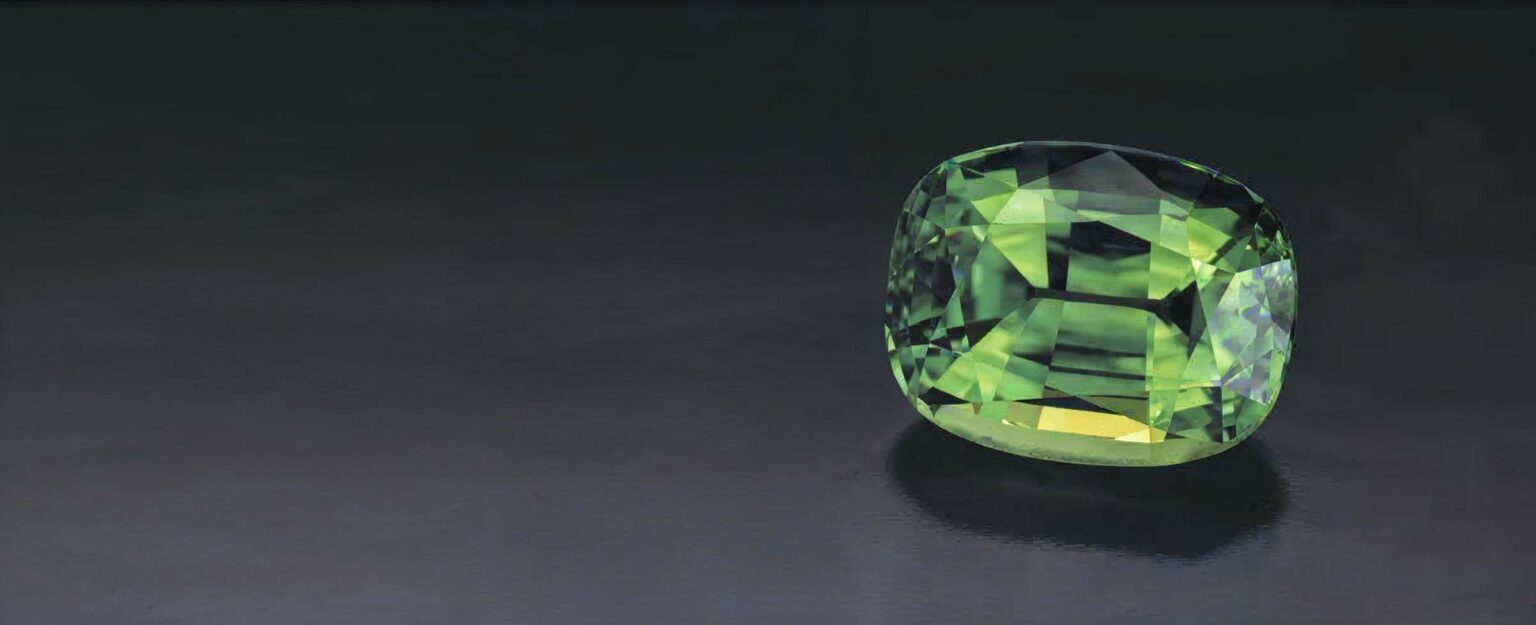

Peridot, which is a member of the olivine family, depends on body mass for color beauty. With availability now almost completely restricted to smaller sizes, few stones possess the green, one Miller likens to “late-summer grass,” that has been prized in this gem for centuries.

So prized was this saturate green that one of antiquity’s favorite compliments to peridot was to mistake it for emerald. A few jewelry historians are now convinced that some, maybe all, of the emeralds Cleopatra was famous for wearing were peridots from just offshore of Egypt. An one farm, dug large gem, for centuries believed to be an emerald, looming the shrine of the Three Holy Kings in the Cathedral at Cologne was finally identified as a peridot.

Alas, this take-me-for-emerald green is almost never encountered in peridots under 10 carats. To find stones with such color, one has a choice of two spots where production has been tried, or headed toward, a virtual standstill in recent years: Egypt and Burma.

The oldest and most celebrated source is St. John’s Island in the Red Sea, some 34 miles off the coast of Egypt. Production in modern times peaked by the late 1930s and tapered off to practically nothing in 1958 when the mines were nationalized. Although sporadic parcels of St. John’s peridot still come on the market now and then, it is not known if this is new or old production. Most assume it is the latter. That is why St. John’s has a mystique among connoisseurs for its peridot that is very much like that of Kashmir, a played-out source spot in northern India, for sapphire.

For new production of exemplary peridot, connoisseurs must depend on barely active Burma. Thankfully, the country’s peerless reputation as a ruby, jade and cultured pearl source has rubbed off on peridot.

Nevertheless, some traditionalists deny Burma peridot full parity with the Egyptian variety. While acknowledging its ideal color, they note that Burmese material is usually less clean and hence less brilliant than that from St. John’s.

Burma stones tend to have carbon spots and a ‘rain-like’ texture in them that keeps a good number of them from being gems,” Miller says. Gemologists variously describe this brownish, sometimes grayish texture as “dust” or “pepper.” But whatever it’s called, it can impart a sleepy or hazy appearance to a stone—although individual specks are not always visible to the naked eye. For this reason, clarity is an extremely important factor when buying peridot.

The Burma quest

The norm for most peridot mined today is a lighter yellowish-green color, often reminiscent of a 7Up bottle, that is far less likely to invite comparison to emerald. These stones almost invariably come from the San Carlos Indian reservation in Arizona. To find emerald-like stones, one must look to Burma.

The quest for Burma material takes dealers to Thailand, Burma’s neighbor, where they buy gems smuggled across the border and down into Bangkok. Most stones that dealers see are tinkered with roughs that have crude tables and bottoms facets but are a long way from being finished gem stones. “The partially cut peridots we buy must generally lose another 50% (of their weight),” Miller says. “But at least the table lets you get a good idea of the color inside the stone.”

But even peridots which have supposedly been fully cut by the Thais often need trimming to unlock more brilliance. Since such trimming adds on to the per-carat price of the final product, dealers less keen on perfection settle for somewhat flabby peridots.

No wonder, Jewelers used to paying as little as $15 per carat for bright, clean, well-cut 1-carat Arizona peridots may be nonplussed at charges of $100 to $150 per carat for well-above-average 10-carat Burma stones. And 10 or so carats more and the price can easily jump to $200 per carat. If you can find best-of-the-breed stones, their prices can easily run 40% to 50% higher. The quantum leap in cost is due almost entirely to rarity.

With the cost of Burma peridot so high relative to that of Arizona, be careful when you buy this gem. While certainly a value element, Burma origin does not of itself justify top prices. Be on the lookout for texture in Burma stones, a sound reason for haggling down the jeweler’s part. Further, don’t pay top dollar for dark or olive colors.

When selling peridot, remind customers that this stone is relatively soft (6½ on the Mohs hardness scale) and should be spared rugged, regular wearing if mounted in rings. Jewelers who do their own gem setting or jewelry repairs may also be guilty of peridot abuse should they forget that this gem is extremely sensitive to rapid temperature changes. Many peridots have been destroyed at the bench because jewelers containing them were dipped into a cold solution after soldering. Blench them should also a note that peridots can lose their polish if they come in contact with commonly used hydrochloric or sulfuric acid.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 36.6-carat Burma peridot shown in the header image is courtesy of R. Esmerian Inc., New York.