Real estate wasn’t the only casualty of the 1981 news that the rule of Hong Kong would be transferred from capitalist Britain to Communist China in 1997. The island’s thriving white opal market was trampled in the same panic that killed its 10-year building boom.

For more than a decade, Hong Kong had been the undisputed center for white opal, responsible for cutting at least 90% of the world’s supply. Like most of the colony’s successful businessmen, Hong Kong’s opal czars had fortunes tied up in local real estate and stock market speculation. News of the change in rulership burst both bubbles.

“There were lots of bankruptcies in 1982,” says opal dealer S. David Brookes, S. David Brookes Inc., Darnestown, Md. “Dealers had no capital, so they couldn’t finance old inventories or afford to build new ones.”

By 1985, estimates Gerry Manning, Manning Opal and Gem, New York, the number of cutting firms in Hong Kong had shriveled from more than 100 to years earlier to under 30. Even so, the world opal market remained remarkably composed. Australia, whose Coober Pedy and Andamooka mines account for at least 75% of the world’s annual white opal supply, responded to the crisis by cutting back mining to around 40% of pre-crash levels. That kept the glut of opal temporarily in check. Moreover, American, European and Japanese dealers quickly moved in to mop up any excess.

In the end, Hong Kong’s opal woes were purely domestic, having far more to do with fear than fashion. Most, if not all, of the island’s opal dealers and cutters are Chinese refugees or their children who left the mainland after Mao Tse-tung’s takeover in 1949. Many escaped the worst of the 1982 crash still chose to sell out, lock, stock and barrel and move to places like America, Canada and Australia, not soon likely to be deeded over to the Communists.

Ironically, the meltdown of Hong Kong’s opal market has been followed by a modest surge of opal sales—after years in the doldrums. Be advised, however, that “doldrums” in the opal market means something entirely different than it does in, say, the diamond market.

Pretty for Pennies

Throughout the 1980s, inexpensive karat-gold colored stone earrings have become more and more of a fashion mainstay. Mass merchandisers have found opal an ideal choice for such earrings. For less than $5 per carat, often under $1 per stone (mind you, these are bulk prices), white opal provides one of the cheapest and most abundant colored stone options, especially for finished karat-gold goods in the $20-$40 retail price range. Indeed, an important Providence, R.I. maker of such earrings tells us his already robust business doubled in one year recently, then jumped another 20%, the following year. “I’d have to say opal is coming back,” he declares.

Actually, it never really went away. From a volume standpoint, opal has always been a major mover. Even in its off years of the late 1970s and early 1980s, white opal was a costume jewelry staple. But no one noticed because all the volume translated, Brookes estimates, into less than $50 million here, $100 million worldwide. Much of what was sold in the off years was essentially low-end material costing only $2.50-$4 per carat. According to Manning, this opal takes two basic forms: milky white with pale multi-colored pinfire, or blue green to green with broad flashes of color.

Because a large amount of low-end opal is used in earrings, easier-to-match pinfire is used more often than broad flash. At present, calibrated fancy shapes (ovals and pears) in 6x4mm to 8x6mm sizes (25-80 points) hold sway, a departure from the past. Until very recently, rounds (between 2-4mm) were the hottest shape. “Now they’re dead,”‘ com- plains the Providence, R.I. earring maker.

Up the Ladder

Jewelers who pride themselves on quality will probably not be happy with largely opaque, pale, no-color-play opal costing $3-$4 per carat. In fact, they may have to pay three times more to begin to get stones with an interesting array of color and some translucency. For our tastes, stones that boasted foreground reds, greens and blues with real fullness start at around $25 per carat in fancy shapes up to 7x5mm.

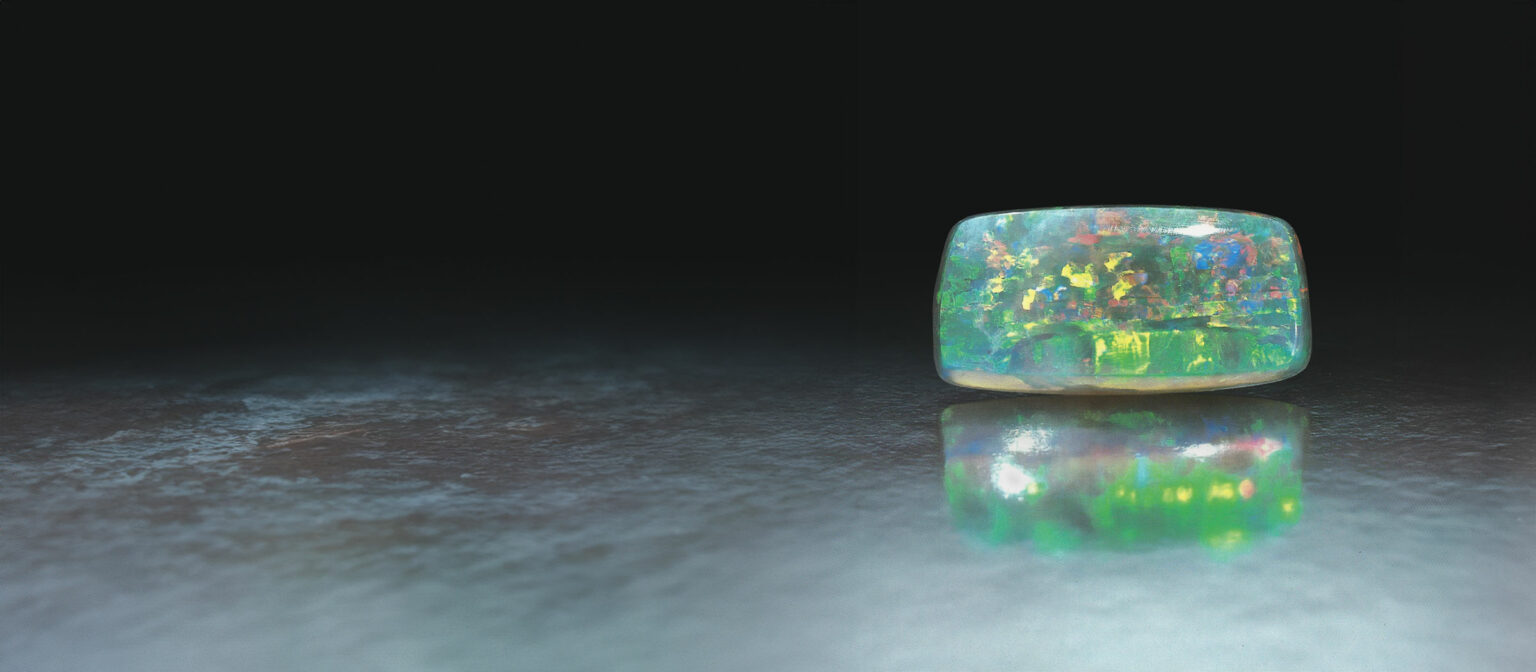

The next step up is what dealers call “crystal opal.” This term refers to the look and not the structure of stones. Costing generally between $40-$60 per carat in smaller fancy shapes and $50-$125 in larger fancy shapes, these opals sport, in Manning’s words, “a translucent glass-like appearance with full colors seemingly suspended in a transparent base.”

But “crystal opal” is only one of the varieties of better opal. The finest usually show no identifiable background color—just a continuous, unbroken array of vivid color patches or patterns. Expect to pay $100-$150 per carat for such material in calibrated goods, depending on size. Larger free sizes can command up to $375 per carat.

Although commercial-grade opal is largely what jewelry manufacturers use these days, there seem to be strong stirrings of interest in better goods. “Providence is definitely up-grading,” Manning states. Such upgrading means that manufacturers are overcoming past resistance to opal based on what dealers say are exaggerated fears about durability.

Improving the odds

To be sure, many white opals crack, mainly through dehydration. But the problem can be minimized a lot more then jewelers think. It all has to do with dealer quality control.

First, the knowledgeable dealer knows which locations in Australia produce the most stable opal (Andamooka is famous for such stones), and shops accordingly. As an extra safeguard, Manning holds all polished stones for several weeks and returns any that crack.

Second, because those opals that crack tend to do so sooner rather than later, the responsible dealer will refrain from selling newly purchased opal polished stones for a certain period of time to let nature weed out any losers. Dealers we interviewed call this procedure “curing” and subject both rough and cut stones to it.

Unfortunately, the dealer’s ounce of prevention is often undone by the retailer’s pound of abuse. Since those opals with a high water content are the most prone to cracking (also called “crazing”), prolonged exposure to bright lights in a closed, unventilated showcase is an invitation to trouble. Thankfully, cracks are often skin deep and can be buffed out on a polisher’s wheel.

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The 10.74-carat Australian crystal white opal shown in the header image is courtesy of Manning Opal and Gem, New York.