At least 70% of the typical Japanese cultured pearls are made in America—namely, from the shell of a freshwater Mississippi basin mussel (naiad is more correct) that has been processed into a bead that forms the pearl’s nucleus.

Divers who find these mussels often cook them open in hopes of finding natural pearls and then selling them to various pearl companies that specialize in the freshwater variety. These days, most such firms are found in Tennessee, perhaps the biggest population stronghold for freshwater natural pearls. In fact, Ed Harvey, E.B. Harvey & Co., Knoxville, Tenn., says 80% of the freshwater pearl jewelry he makes is sold to jewelers in eastern Tennessee.

But once out of areas where they have long been fished—mostly in the Mississippi River tributary system—consumer interest is a shadow of what it was, say, 80 years ago when natural pearls were a jewelry store mainstay.

Today, however, freshwater natural pearls are an endangered gem species, victims of both ecological mayhem and over-fishing in the waters where they are found. According to John Latendresse, American Pearl Co., Camden, Tenn., “Production is less than 1% of what it was 40 years ago in the heyday of freshwater pearl fishing.” So where do the freshwater pearls come from that dealers need to meet what they say is increasing demand?

Follow the River

Latendresse, who is considered the present-day dean of freshwater pearl dealers, is lucky. After World War II, when the Japanese pearl growers began to blitz the U.S. market with cultured pearls, natural pearl dealers panicked. Realizing they were ready to dump goods, Latendresse, in conjunction with the late dealer Morris Hanauer, bought all the dealer stocks of natural pearls they could find. Today, Latendresse lives off the remainder of those buy-outs. Latendresse is an exception. Other dealers who specialize in freshwater pearls find the getting rough—but also romantic.

Take St. Louis, Mo. specialist Lowell Jones, who in the last six years has emerged as one of the leading lights in what he calls “the freshwater pearl movement.” Formerly a precious stone dealer, he left that market when gem investments companies invaded it during the hard assets mania of the late 1970s. “I saw pearls starting to make their move and looked for a niche in that market,” Jones says.

That niche: American freshwater pearls. To secure it, however, he had to start buying estate goods in backwater towns all over the United States and Mexico. Like Latendresse 30 years before him, Jones took to leaving cards with bank loaners in paper river towns and cities and advertising in local newspapers. Gradually, owners of freshwater pearls contacted him and he would fly down to inspect their goods. If interesting to him, he would begin negotiations.

While he was finding sellers, Jones was also finding buyers. Many of his clients are super-rich Arabs whose love of pearls is nurtured by the majestic status this gem occupies in Islamic mystical lore.

Evaluating Freshwater Pearls

For both the veteran and newcomer alike, quality in freshwater pearls depends on five factors. According to Maurice Shire, Maurice Shire Inc., New York, those factors are size, shape, color, luster and cleanliness.

Because freshwater pearl production is down precipitously in the last 30 years (at least 20 species of American pearl mussels have died out since 1900 and 20 more are now listed as endangered) and because mussels live shorter lives (due to toxic wastes), U.S. pearl sizes aren’t what they used to be. Nowadays, says Jim Sweeney of American Pearl Co., sizes over 6mm in symmetrical and 9mm in baroque (asymmetrical) shapes are considered large and therefore rare.

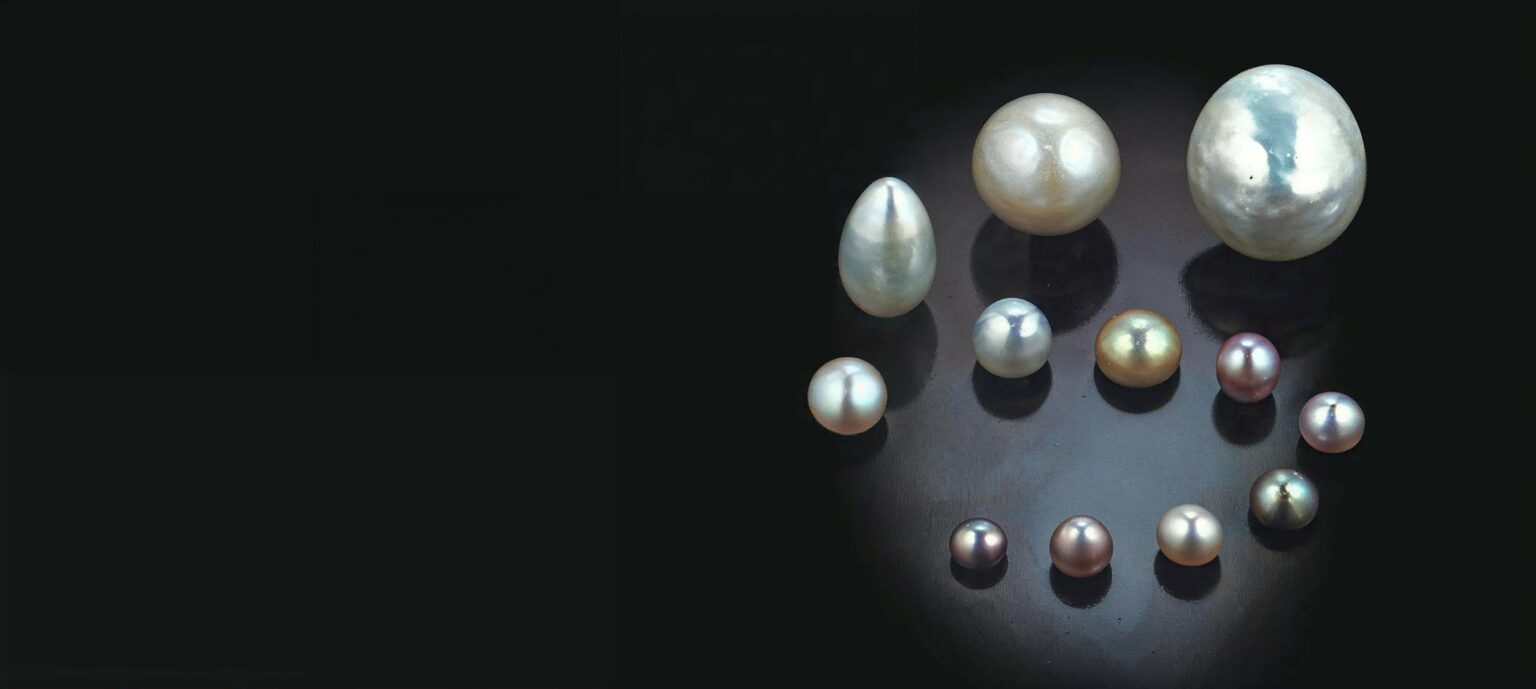

Unlike cultured pearls, the predominant shape of freshwater pearls is baroque, accounting for at least 95% of the production now and perhaps always. Symmetrical pearls are most apt to be button- or pear-shaped than spherical. Of the baroque shapes, the majority are elongated, resembling bird’s wings and dog’s teeth. Most prized, Shire says, are what dealers call “classic” shapes, two in particular: the rosebud (a high-domed round-to-oval pearl with lots of ridges and bumps on the top) and the turtle-back (a turtle-shell shape with a smooth back).

Color in freshwater pearls has the greatest range and variety of any pearl. Yet 90% of what is found today is white, with some cream and silvers. Far more rare are the blacks, greens, blues, oranges, pinks, purples and lavenders. When judging color, dealers look for overall body color and overtone.

It is hard to completely separate color in pearls from their luster, or basic brightness. Technically speaking, luster is the amount of white light from the pearl reflected back to the eye. At its best, luster looks like “a drop of mercury,” Sweeney says.

Don’t confuse luster with orient, the amount of iridescence observed when a pearl is moved under the light. Orient is usually stronger in natural pearls because they have the requisite depth and transparency of nacre (the substance secreted by a mollusk to make a pearl) to allow for the light penetration and breakup needed to produce iridescence. Orient is strongest in baroque natural shapes where surface irregularities heighten it.

Last, cleanliness plays a minor role in determining a pearl’s value. Ideally, a pearl should be free of surface discolorations, holes, pits, scratches, gouges and the like, on its surface. Due to rarity, some are acceptable, especially in large sizes.

Because freshwater pearls are so rare, their prices tend to be higher than the cultured variety. Nevertheless, we found that much freshwater pearl jewelry is still very affordable. Because freshwater pearls are principally baroque jewelry pieces tend to be free-form, generally using 10k or 14k gold and occasionally 18k gold and platinum with finer pearls. Both E.B. Harvey and American Pearl Creations (the jewelry subsidiary of American Pearl Co.) offer rings for under $100, a few even under $75.

Freshwater pearls remain a regional gem with interest confined to areas where they’ve been fished. But once in a while, some are so spectacular in size, color and shape that they take on world-class status. Indeed, Jones concentrates on pearls that he can sell at auction and through international private referral. “There,’ he says, “interest in freshwater pearls is the greatest it has been in years.’

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

The American freshwater pearls shown in the header image are courtesy of American Pearl Co., Camden, Tenn.