Recently, the decade-old battle between aquamarine and topaz—the prime movers among pastel-blue gems—has seemed so one-sided that some of America’s fiercest aqua partisans are doubting, if still not deserting, the cause.

As the blue beryl has steadily lost ground to far less expensive but no less beautiful blue topaz, some firms that specialize exclusively in aqua have begun to pledge allegiance to both blues. One of them, Kaiser Gems, Los Angeles, once around 40-50% of its 1985 sales to blue topaz, the first year it ever sold blue topaz.

However, such accommodations to topaz are not always defections from aqua, although they might seem so. The aqua market is at war with itself.

Ever since the influx of new-breed aqua from African countries like Nigeria, Zambia and Zimbabwe started in 1982, a growing number of jewelry retailers and manufacturers tend to snub the Brazilian variety, for years the market’s mainstay. Gem dealer Doug Parker of the William L. Kuhn Co., New York, says almost all the aquas he buys for his company’s new owner, Honora Inc., are African stones cut in Israel. “They have lovely deep colors never thought possible in 1 to 2-carat sizes and prices just as attractive,” he declares. “I’m buying remarkable 6-7mm rounds at around $200 per carat.”

Beautiful bargains in African aqua have hurt sales of South American stones, which rarely possess comparable richness of color in currently more-preferred smaller sizes. And as sales of Brazilian aqua fall by the wayside, so have cherished notions about this gem as a whole.

Small, Dark and Handsome

Truth is rarely absolute in the gem world. Gems from a newly discovered locality can challenge generalizations about a species.

Until just recently, the gem world based its assumption about aquamarine almost exclusively on acquittance with the Brazilian variety. As a result, it was believed that aqua had to come in larger sizes, 10 carats or more, to realize its deepest, fullest color. True, deposits like the Santa Maria and Colonel Murta in Brazil yielded darker-color small stones, but such stones were the exception to the rule. Larger crystallization and bigger body mass were considered prerequisites for saturate-blue aquamarine.

Then stones from Kenya, later followed by stones from Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), Nigeria, and Zambia, started appearing on the market. Most of them came from Germany, long a principal cutting center for African gems.

“African aqua broke all the rules,” says gem dealer Abe Suleman, Tuckman International Ltd., Seattle. “We were seeing spectacular deep blue colors in stones as small as 50 points. Brazil had little or nothing to compete with these goods, far as color goes, in sizes under 5 carats.”

In no time at all, Suleman had switched from Brazilian to African goods in small sizes. One powerful inducement, besides deeper color, was lower cost.

“Aqua had been a popular inflation hedge in Brazil and prices were at all-time highs,” Suleman continues. “African material was available for far less money. This may have contributed to the collapse of the Brazilian aquamarine market in 1982.”

The introduction of African aqua couldn’t have come at a better time. Still in the throes of a recession, the U.S. jewelry market was shifting from larger free sizes to smaller calibrated ones. Using African aquas, jewelry makers could give customers deeper colors in economical 1- to 2-carat sizes. Although the recession is over, this trend still holds sway today. However, signs point to a resurgence in somewhat larger sizes.

Back from Plentitude

African aqua was not only a godsend for jewelry manufacturers. It gave a colored-stone cutting center like Israel a new lease on life just when supplies of Zambian emerald, for years practically the sole sustainer of Tel Aviv’s precious stone market, began to dry up. Israel is not the force in aqua it is in emerald. But dealers like Parker who have seen Israeli-cut aquas describe the workmanship as “superb.”

The real power in African aqua is Idar-Oberstein, West Germany. A peer of Israel in terms of cutting, it has no peer in terms of supply. Paul Ruppenthal of A. Ruppenthal KG in Idar boasts of ample backlogs of African-variety aqua. A tour of his storerooms proves it. And Ruppenthal is not alone. Nearby, dealer Julius Petsch Jr. shows us sack after sack overflowing with African aqua rough, enough, he says to keep him going well into the next decade.

But you don’t have to trek to Germany to find plentitudes of African aqua. Periodically, African miners have been known to dump rough on the U.S. market. Such happened in 1983-84 when the U.S. dollar was riding high. Hungry for cash, Nigerian miners sold rough at giveaway prices—often as little as one-fifth that of comparable Brazilian rough. Despite the far lower yields of Nigerian rough, dealers scooped up the material. Even Brazilians were taking advantage of the bonanza.

Blue AU Naturel

Almost unnoticed in the early euphoria about African aqua was the fact that all, or almost all, of it has been spared heating, something obligatory for Brazilian material. Until then, it had been a truism that virtually all aqua was treated.

Suddenly that truism was a half truth. Many African aquas had already attained a desirable blue in the ground. So trips to the oven were unnecessary. True, some natural-blue stones had steel-grey overtones, but heating didn’t help. Besides, the market began to adjust to African strains of blue. “Jewelers didn’t like the dark green of Zambian emerald at first either,” Parker says.

Taking a little more getting used to: stones with heat-resistant tinges of green. According to gemologists, the green in African aqua is the result of chromium while that in Brazilian stones stems from the presence of iron. While heating can subdue the influence of iron, it doesn’t alter chromium-induced colors. Thus many of the aquas seen in Germany nowadays have a distinct green overtone. Although we find these stones attractive, purists still prefer pure-blue stones. However lower prices for greenish-blue aquas tempt some purists to experiment.

“It’s ironic,” Suleman says. “Africa may eventually force fresh acceptance of the natural color of most Brazilian aquas, a color dealers have been altering for decades.”

Please note: this profile was originally published in 1988 in Modern Jeweler’s ‘Gem Profiles: The First 60’, written by David Federman with photographs by Tino Hammid.

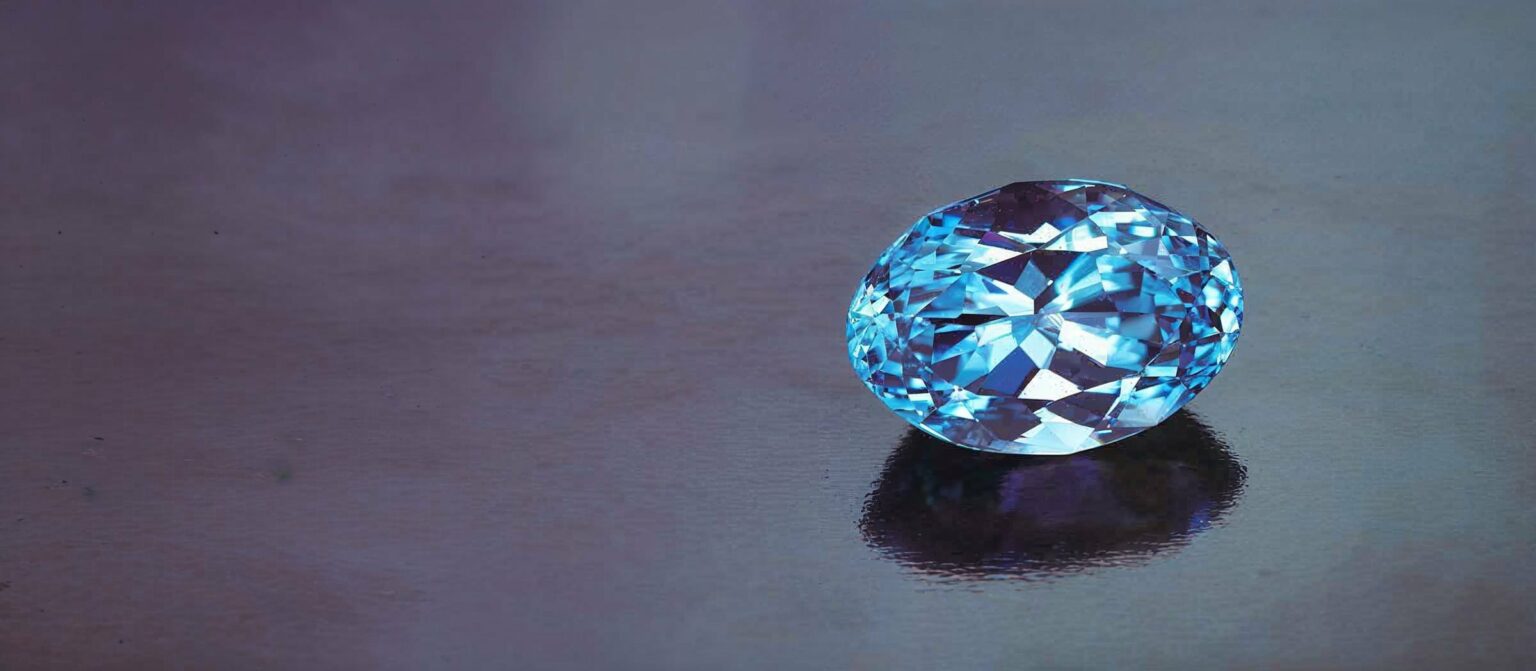

The 4.9-carat African aquamarine shown in the header image is courtesy of Tuckman International, Seattle.